Splaiul Tudor Vladimirescu no. 9

The house belonged to Titus Olariu, lawyer and former prefect of Severin County.

Listen to the audio version.

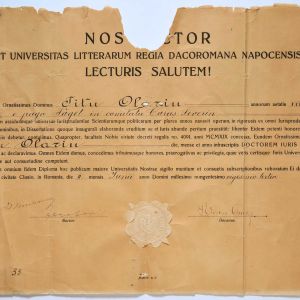

Born in the family of Sebastian Olariu, the archpriest of Făget, Titus Olariu (1896 - 1960) studied at the Romanian Greco-Oriental Gymnasium in Braşov, graduating in 1914 with the baccalaureate exam, being a colleague with Lucian Blaga, D. D. Rosca, Ionel Jianu, Coriolan Băran and Andrei Oțetea.

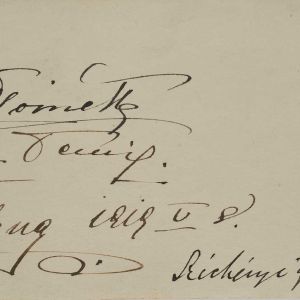

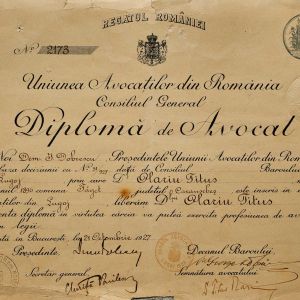

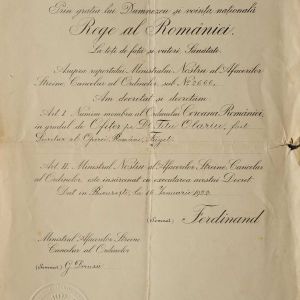

Countess Ilona Széchenyi made the portrait of the lawyer Titus Olariu in 1919, during the First World War, when the young man fell with the airplane on the estate of Counts Széchenyi. After participating in the First World War, Titus Olariu was baritone at the Romanian Opera in Cluj, Volksoper in Vienna, Staatstheater in Dresden, member of the National Peasant Party, prefect of Severin County (1932-1933).He was a magistrate, counselor and president of the Administrative Court of Timişoara (1939-1949) and member of the Reunion of Banat Singing Reunion in Timişoara under the musical direction of Sava Golumba.

Titus Olariu was a political prisoner between 1952-1954. Later, he performed as a chorister and conductor of the Choir of the Metropolitan Cathedral of Timisoara. Lawyer Santuzza Olariu, daughter of Titus Olariu, donated the documents of the Olariu family to the National Museum of Banat in 2018.

The construction of the palaces on Splaiul Tudor Vladimirescu is related to the demolition of the city's fortifications, which took place between 1899 and 1910, as a result of which the boulevards connecting Iosefin-Elisabetin and Cetate are furnished with monumental buildings. The ensemble to the left of the Trajan's Bridge, which also includes the Olariu family house, a bridge that forms the border between Iosefin (to the right of the bridge) and Elisabetin (to the left of the bridge), was built in 1900, with its specific currents from Art-Nouveau to Jugendstil and SecessionThe building of the Olariu family has a slightly geometric Secession style, the details chosen are vegetal, used for hollow frames, or in the composition of the horizontal strips that accentuate the different levels or the base of the bay windows.

Bibliography

1. Constantin Tufan Stan - Titus Olariu. The artist and his era, Timisoara, Anthropos Publishing House, 2008.

2. Lazăr Gruneanțu - Lawyers of the Timiș Bar 1875 - 2015. Lexicon, Timisoara, ArtPress Publishing House, 2017.

3. Mihai Opriș, Mihai Botescu, Historical Architecture in Timișoara, ed. Tempus, Timișoara, 2014

Listen to the audio version.

Pia Brînzeu, Family Journal, Manuscript

Stop 14: The family residence of Titus Olariu, Doctor of Law, on Splaiul Tudor Vladimirescu

March 15, 1944. Schniffi, my mother’s puppy, is anxious. Mother knows this means that the alarm announcing the bombardments will soon follow. She doesn’t wait for the sound of siren, but she pulls my brother out of his pram and, together with my grandmother, she heads to the basement shelter. In here, the servants’ rooms are tidy. Just as they left them when they went away. Even Grandmother, when she took the rugs down, she wrapped them in newspapers soaked in petroleum to keep the moths away, and she wrapped the china nicely, arranging it into boxes, each box bearing a label with its contents. She also took down the stained glass windows from the dining room, so they wouldn’t break in case of an attack.

Both ladies sit quietly, lost in thoughts, waiting for the air raid to end. They have no future ahead of them. They were left alone, with one child to raise, without Grandfather and without any income. How long will they survive on selling things from the house? A year or two? Still, Mother believes in her lucky star: she was born on Sunday, and those born on the day of the Lord are always lucky. Every time it has been hard for her, God has always been close to her.

They are sure that at the end of the war they will put the windows and rugs back in their places. What they do not know, though, is that, for fear of the Communists, a part of the china, silverware, and jewellery will remain boxed up. Besides, our house will end up invaded by tenants. Two of the rooms in the basement must be vacated for them, and so the boxes end up in a pile, stacked one on top of the other, in the other two rooms. Dust will slowly gather on them, the electric wiring will also be damaged, and the door lock will barely work anymore. As a child, I didn’t dare to enter the darkness and the dirt which accumulated for decades on end. But I was fascinated with the content of the boxes. I knew they contained beautiful things, but Grandmother wouldn’t let me open them. They couldn’t be brought upstairs, because there were three other sets of tenants in the house: an engine driver, with his wife and a daughter my age, a student at the Polytechnic, and an engineer. Soon my grandmother will die, and mother won’t know anymore what lies in the basement and will be too old to do something about it.

It is only forty years later, when I move back to my parents’ house, that I will have the courage to go down into the long forgotten rooms. The dried up fur of a cat, dead under a box which had fallen on it, welcomes me with its empty sockets and makes me feel like in Great Expectations. Other than that there is litter thrown through the cracked window, which gives onto the street, books from the beginning of the century, medical instruments, laces, embroidered bed sheets, fur muffs, hats, silver-handled walking canes, monogrammed men’s socks. I browse through them with great pleasure, fascinated by the atmosphere they bring back to life. I feel that I need to save their beauty, to bring them to light, to place them behind some museum showcases. I will also sanitize the rooms, which have once again become “like back in the old days”. But my zeal is excessive. Because of this zeal, the whole atmosphere of the dusty basement is lost, as it also happens with archaeological sites open to tourists, or with the objects showcased in museums. None of the people looking at them knows what it meant to find them and take them out one by one from the place where they have lain untouched for such a long time, to remove the dust thinking about the people who used them and to take a plunge into their lives, discovering other desires and loves, other purposes, vanities or miseries than those that accompany our own present.