The Union Square (Domplatz) had unusually large dimensions, compared to the size of the fortress, which served to highlight the baroque aspect of this space.

Listen to the audio version.

The Baroque-style Union Square (Domplatz), which appears as a sketch on the 1733 plan, was later finished, but larger in size than specified in the above plan. The unusually large dimensions of the square, compared to the size of the fortress, served to highlight baroque style of this space. The representative buildings located on the four sides of the square offer a suggestive image of the Timișoara architecture from the 18th century, even if over time these buildings have undergone changes. The strong points of this Baroque heritage are the Roman Catholic Dome, on the east side; the Serbian Orthodox Episcopal Cathedral on the west side; The Baroque Palace (headquarters of the Banat Country Administration in the 18th century), on the south side, and the typical 18th-century buildings on the north side of the square.

In the central part of the square is the monument of the Holy Trinity. Banat administration councilor Johann Anton Deschan von Hansen commissioned this statue to commemorate the 1738-1740 plague epidemic. The statue was sculpted in Vienna in Baroque style and then transported on the Danube, the Tisza, and the Bega waterway and mounted in the Transylvania Gate Square on November 21, 1940. Somewhere between 1755 and 1758, the statue was mounted in Union Square.

Bibliography:

Hans Diplich, Die Dreifaltigkeitssäule in Die Dreifaltigkeits- oder Pestsäule in Temeswar. Stationen einer Wiederentdeckung, Ed. Landsmannschaft der Banater Schwaben, München, 1996.

Mihai Opriș, Mihai Botescu, Historic architecture in TimișoaraPrinted by S.C. Tempus S.R.L, Timisoara, 2014, ISBN 978-973-1958-28-6.

Union Square and the Holy Trinity monument

Monument of the Holy Trinity 3D

Robert Șerban

I’m waiting

for a table to open up

I’d have a drink

It’s hot I’m thirsty

I’m waiting and waiting

nobody wants to leave

everybody’s got in front of them cups glasses bottles

which all seem full

I got old

I don’t know anyone anymore

who’d beckon to me to come over and have a seat

I’m waiting and waiting

thirst makes me nervous and anxious

the sun’s getting tenser

I stop a waitress

I mumble that I really want

to write a poem

and then I whine

will you please help me?

intrigued she looks at me

takes a step back

measures me up and smiles

and suddenly kisses me on the cheek

you will succeed now

sir

June 2022

“In Timişoara, I take the trolleybus 11 from the railway station, but right on Brediceanu Street it gets a flat tire, and from there I start running, behind the Military Hospital, on Gh. Lazăr Street, across Unirii SquareUnion Square, behind the Dicasterial Palace and the Bastion, until I get to the bust statue of Sălăjan. Gorgeous and burdened by memories, in the golden light of an autumn noon, with the Dome and the 18th-century buildings, clean, hieratic, silent and almost deserted, Union Square revives my admiration and that deep-rooted, strange and sweet and sad love for this unrivaled city.” (Radu Ciobanu, The Late Shore – A Journal (1985-1990)Deva, Emia, 2004, p. 129)

Eugen Bunaru

Crossing Union Square

(poem in prose)

In memory of my grandfather, Gheorghe Popa

It happened a few years after the war. In the 50's, but what did I understand back then about all this?! Uncle Mircea once asked me, trying to be funny, at a family lunch on Sunday, what I want to be when I grow up. I answered promptly: soldier or Russian, I don't remember exactly. Platoons of Soviet soldiers trotted every day singing warrior marches with their guns on their shoulders on the streets of the city. My family went silent. Later, my grandfather whispered some things to me ... I used to call him Taica. He often took me for a walk. It was kind of an inlaid ritual in my mind, considering I had barely turned 4 or 5 years old. We were crossing Unirii Square.

My eyes were always stuck on the glow of the towers of the two churches that solemnly mirrored each other: on the left the Catholic Dome with its stone severe lacework, on the right - the Serbian Church of St. Nicholas gliding supple above the sky. In the middle of the Square - the fountain with healing water, where children would always cool and run nearby, while white and multicolored birds flew around. We were walking into Mercy. We could see imposing gentlemen and elegant ladies, discreetly wrapped in the fabric of a French perfume. I was arriving in Sfântul Gheorghe square. Here we would always stop, every time, for a minute, two or three. My Grandfather was watching, who knows what, on the opposite square, with pigeons gurgling and taking off again and again, after a typical eternity, the flight to the open sky between the two imperial palaces. We started walking again. He had a thin black cane with a silver stain - he said it was ebony, and that he had inherited it from his father, who also had it from his father - basically, an ancient family piece.

I was (I don't know why) shivering when he would hit the sidewalk lightly, making a melodious, strange sound that vibrated for a second or two into the spring air. I loved his gentle Santa Claus face and secretly admired his white slightly twisted upwards moustache, like an old Caesarean clerk. He had an aura of contagious bonhomie. He was always silent with his face lit by a discreet-mysterious smile. At home, he preffered to retreat to his room where we could hear, then, for a while, the playful, azure (I think) monody of translucent flute sounds. From time to time, on a bench, in the fragrant shade of a lime tree, he would tell me with a bizarre pathos about Napoleon Bonaparte, about the fatal war in a huge, polar Russia. Finally, we would arrive - it was just two steps away - in the Old City Hall Square. Here he would stop to buy - I think - the local newspaper. From time to time, he would take off his hat and leaning slightly to the left and to the right he would say : “I have the honor to greet you all!”

And we left further to reach the Center, on Corso. The ritual was repeated: "I have the honor to greet you, Dr. Domide!" "Much respect, Mr. Popa!" This was the the answer that came from the huge, statuary height of the illustrious physician. Step by step, we crossed the small park in the Opera Square. It was a torrential noon. The bells were ringing. The air vibrated all around. We entered the Cathedral. We lit a candle and prayed to God for Uncle Severus (I had never seen him except in a family album) to return, and he finally returned home from the front in World War II. From Mother Rusia. From the huge, crushing Soviet Union. I didn't understand anything anymore. There was a tiny, silver shining tear on my grandfather's cheek. It happened a few years after the war. By the 1950s.

On the left side of the picture we can see the Scherter House, that being its last name to this day. Originally, it was the home of the Deschan family, which was of French origin. This Deschan was an important personality. He was ennobled by Empress Maria Theresia and from "de Jean", his name was changed to Deschan von Hannsen. This family built the monument of the Holy Trinity which is still located in Piaţa Unirii today.

In the foreground of this picture, on the right, you can see the Holy Trinity Statue. The foundation stone of this monument was laid on November 23, 1740 by the councilor of the local administration at the time, Johann Anton Deschan von Hannsen, who initiated the creation of the monument. The statue commemorates the end of the plague epidemic that devastated Banat. That is why it is also called the Plague Statue. The monument is composed of a tall, triangular column, symbolically decorated, on which the Holy Trinity is enthroned. The Father and the Son hold the heavenly crown above the head of the Blessed Virgin Mary kneeling at their feet. At the base of the column we can see the statue of Saint Nepomuk, and below - the statue of Saint Rosalia. At the same height as Saint Nepomuk are the statues of King David and Saint Barbara, the patron saint of miners. The triangular plinth is guarded by the statues of legendary protective powers: Saint Rochus, a saint of the plague, because many people prayed to him, Saint Sebastian and Saint Charles Borromeus. On the three sides you can also see relief sculptures, representing the three calamities: war, famine and plague, caused at that time by the Turks. The monument is made out of sandstone, in Vienna, in baroque style. It was brought to Timisoara by water, Danube-Tisa-Bega Canal. This statue was recently restored through the collection organized by the Organization of Swabians from Banat, settled in Germany, while the rest of the money was sponsored by the government of the state of Bavaria. (...)

(Else Schuster interviewed by Adrian Onică)

Else Schuster Adrian Onica

(And in Union Square there was a market?) Union Square... that is, the Cathedral... was a market. My mother used to go there all week, she would come with the baskets from there, the peasants from the surroundings and we had a Frau (lady) or another Frau (lady) who brought sour cream... More sweet cheese and sour cream were bought. And vegetables and fruits. Apples were bought from such carts from Romanians who came from the mountains.

Mariana Sora (b. Klein, 1917) interviewed by Smaranda Vultur at Băile Herculane in 2001. Third Europe Archive, BCUT.

(And did your parents go to Timişoara for shopping?) Through Union Square, where the church is, there was a vegetable market, where my mother used to come to shop; everything that was for sale was put on the ground, there were no tables, it was simpler. Yes, that's where people used to go.

And where the pharmacy is in Union Square, there was also a row of shops - I know that, because after I got engaged to my husband, he bought me a thicker hood from there. I knew that the Jews were the owners of the shops and they would give you a chance - that's what they did, so that people would buy their stuff - if you didn't have the money, they would write your name on a calendar, they would give you the products and when you had the money - you would pay for them, so the Jews were very decent! They also sold everything for cheaper or they gave you some gifts, the world would was very happy with them. There, in the village of Murani, how... - my mother had twelve brothers before, in the end there were seven left and they were poor. There was a very rich Jew in Murani, everyone in the village knew him, his name was... Hamer. The village helped her so much, they would give away food and plenty of goodies, the village helped her a lot! He was a good man! He had a lot of wealth, plenty of land, the poor people worked for him, but he never cheated them, he paid them properly and helped them. If she didn't have food for her children - I know my mother used to say - she promised to give it back next year, like this year, for example, it didn't bear any fruit. And he always had it in the barns, considering he had a lot of soil, he would never run out of food. It helps a lot! (So, here in Timișoara, you would also get free gifts at the store?) He also gave away gifts, smaller gifts, to the children.

(Did you come to Union Square too or did you never see it until you got married?) I did come. After I got married I also did. I know that I came - that I came back with watermelons, because we put a chain all year. A chain is half a hectare. That chain of land brought us as much as the rest of the land would have. It was so good to have it. Just like it is now, there is something to eat. We used to come to Hay Market, with a cart full with watermelons, two or three times a week. I know that I came once and - and there were some thieves around - and they stole all my money, and I cried so much, I cried so hard, and my mother was at the market, I know that she gave me some money, so I went to my in-laws and I cried that I can't go there without money anymore... I had like a little bag under the apron, maybe you saw that they use it at the market. How did they steal from me?!... They came in to change the money, and I gave a bigger sum, and he didn't give me the change. I don’t even know.

I would come in early morning and stay until noon, until the goods were sold. Union Square was paved with stone and everyone put their goods there... there was a row with cream, another one with tomatoes, that's how you lined up. I had tomatoes in the village, I put them in the field and no one watered them. I would use those big baskets, when I brought the watermelon, I also brought tomatoes, because where we grew the watermelon, we also had tomatoes. And they were easily sold, people bought a lot, they were not as expensive as they are now.

Ana Vasin (b. 1928, Cernăteaz) interviewed by Mihaela Sitariu in 2000 in Timișoara.

Third Europe Archive, BCUT.

(....) So the Banatian, the Timișoara man is a man of some manners, but not with a pejorative connotation, so to speak. He is a stable man, so to speak, in a certain existential matrix on which, I repeat, this somewhat severe framework…

Architectural?

Yes, without a doubt, it impressed him on his way of existence. Because it imposed a certain rigor and I would argue, here, also through the memories I have from my childhood when I went to visit my grandparents. There, in the daily ritual of my grandparents' existence, I somehow saw - even if, at the time, I had no historical knowledge to refer to, that was not important for my imagination as a child - but I saw, I repeat, an unfolding of gestures, words, moments, small incidents, in fact, an existential-daily ritual, which gave me the feeling of an immutable order, of a discipline that had become a way of life... But a bonhomie, family discipline... My grandfather had a fixed hour to eat, to sleep, he would take out, at mathematical intervals, from his waistcoat pocket, an old Austrian clock, with bizarre inlays and a silver cover, which he would put on his stomach and carefully look at the time in question: when he had to read the newspaper, or when he took his time to relax or, later, when he reserved an hour of sleep. Then there were other, let's say, moments of daily existence... In the evening, a walk, just as ritualistic, using the cane with a silver handle, through Union Square or towards the Cathedral, accompanied by my wife and children, by my mother, Misirca, by her sister, my aunt, Constanța, and by the two boys, Sever and Mircea, the later conductor and composer, Mircea Popa… About this way of life, these "habits" that evoke the world we are talking about, have a counterpart in the literature I read, of course, later and I am referring to Bruno Schultz, Joseph Roth, and several other writers from the space of Central Europe... I would also like to add that my grandfather played in a neighborhood orchestra, where Romanians, Germans, Hungarians, Jews, and Serbs performed together... It was, so to speak, a mini-orchestra that had performances on various festive occasions. I remember - my mother would say that these things happened both on Catholic holidays and on Orthodox holidays... This orchestra, having its headquarters and rehearsal place somewhere in this part of the city, in Unirii Square, made small tours in other neighborhoods, in Fabric, in Iosefin, and even in the communes around Timișoara. So, again, a custom of the place that fits into the specific spirit of the area, and, of course, in the wider space of middle Europe... I was talking about "manners", about that ceremonial, that occurs on Saturdays or Sundays…

My grandfather, after taking his rest hour, had a small program, an hour of rehearsal played the flute, and retired to his room, it was the last room of the house, with furniture and old, massive wardrobes from dark brown wood, and which, also through that solemn massiveness, through small ornaments, spoke of the same spirit or of the same specificity of the area... It was palpable, in all these details, the imprint of what, in fact, I was trying to define... I say this without being tempted to give a picturesque halo to my memories. But, all these details of the interior of the house, the furniture, the paintings, the framed photographs, with men in uniform, with twisted mustaches, spoke of the Chesaro-Craies spirit which, even when Timișoara no longer belonged to that space and that historical era, following the changes that occurred, returning, by right, to the space of the mother country, so to speak, it was still preserved, however, in small therapeutic doses... That flair, that assumed multicultural spirit, in his own natural way, in illo tempore, uninoculated, was still preserved in an artificial, programmatic, thesis way... I will now go back to my grandfather who sang and made his rehearsal schedule, in order to participate in the small concerts that the small orchestra played.

What was the name of Grandpa's family?

It's about the family from the mother's side: Popa, the family was called Popa. My grandfather's name was Gheorghe Popa, and my grandmother's name was Elisabeta Popa. We, the children, my sister, Michaela, and I, used to call our grandfather Big Father, or Father, and my grandmother was addressed as Big Mother.

You were talking about the holidays, the markets...

Yes, the holidays, I especially remember Easter... The Union Square, from my childhood, which is different from the one today, acquired, then, at Easter, a festive appearance, a special charm. I was fascinated by the red eggshells flying here and there on the pavement of the square... I mean, I knew about Union Square from way back when fairs were held there, it was a real market and, on certain days, I think it was on Tuesdays, if I'm not mistaken, and Thursdays when there were some kind of fairs, when peasants would come from the surrounding villages with carts, goods, with various foods - they sold, they traded... It was fair that, willy-nilly, reminded me, in the end, later on, when I read Slavici - it reminded me of that exotic world, full of diversity, from the novel Mara. Because that’s how it was.

Circuses also came to Union Square... Almost every year, usually in the spring, but also in other seasons, more towards autumn, we had some kind of circuses, traveling circuses - which, for us, children, were a massive point of attraction... I was running away from home, I didn't give any explanations to my parents anymore, I was quite independent, even back then... I took advantage, in my unconsciousness as a child, of the fact that my father, a parent with strict principles, was sick and had been hospitalized many times, and this gave me the feeling that I was less controlled, that I was freer…

What do you remember about these fairs?

From the world of the old circuses, I still remember the bizarre characters and moments which today can no longer be seen, even if circuses still come around, usually from other countries, presenting more professional, more selective performances, probably... Back then - we, the children, were fascinated by those dwarves, directly descended from the world of fairy tales, from the immortal Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs story, very appreciated by the children my age, just like those dwarves who did all kinds of funny pranks. I know that for several years in a row there was a fair, who had a special moment of attraction in their show, which made the performance delightful, provoking a flood of applause and exclamations of admiration… and the actors were called: the dwarf woman who sewed with her feet, who would fix the needle with her feet, who combed her hair with her feet, who did various household activities with her feet... I was such a rapt spectator because, at the same time, I felt like I, myself, was part of the show... Of course, the fascination, but also the most intense emotions, were aroused by the "flying" motorcyclists on the wall of death. There was an Italian circus that came almost every year to Timisoara, and set up its huge tent and all its stalls in Unirii Square. There I saw those real wizards of the race on the the wall of death

- they were Italians, as I said - with their supple motorcycles, dressed in black, puffy suits, their figures cloistered under helmets and huge, convex glasses. They started from the bottom, from the base of that bizarre construction, and, accelerating madly, climbed to the top - to the top of the pyramid, while we, the spectators, children and adults, were overwhelmed with emotion to the point of paroxysm, we would literally stop breathing. I still remember the name of their leader, he was on everyone's lips and the most admired of all: Aldo the Italian!

Eugen Bunaru interviewed by Aurora Dumitrescu in Timișoara, 2004, Third European Archive, BCUT.

Listen to the audio version.

No year without meetings in Union Square

I suppose that each of us has at least once met someone in Union Square. It has a strong significance for people who frequent outings with friends, and every summer it's almost impossible to get a seat at a table in that area. Dating with friends has become more of a routine, where we meet in Unirii Square and pace through a walk around the St. Trinity monument to at least catch a free table to linger and admire the beauty of the square with a glass of wine. The hustle and bustle of the market is never tiring, more relaxing. Despite the dozens of people sitting at tables or choosing to wander around, I never felt this market was too crowded.

Unirii Square surprises me every time with its beauty and architectural elegance.

Leucuș Larisa, UPT student, 2023

Ariam and Zephyra

by Maria-Mirabela Urziceanu, 7th grade

"Grigore Moisil" Theoretical High School Timișoara

In the depths of Timișoara, where shadows lengthen in the moonlight, a charming story unfolds about a brave girl, a lost fairy. In a cozy and modest little house, hidden in the narrow and winding streets, there lived a brave, dark-haired and wise girl named Ariam. Like any child she was very curious and used to roam the streets of the city in search of new adventures and fascinating discoveries.

One evening, as her stroll took her through the alleys of the newly discovered neighborhood, she heard a delicate whisper like a bewitching melody. Curious, Ariam followed the sound and came to a secret courtyard where a frail fairy was resting and weeping her sorrow on a damp leaf. She sat alone, gazing sadly at the vault of heaven. Fairy Zephyra had been trapped in the human world by mistake and could no longer find her way home to the magical world.

Ariam, being a generous child, offered to help the fairy. He thought it would be best to take her to the Astronomical Observatory - he had heard that from there you could enter the Universe. Together, they set off through the dark streets. As they drove towards the Observatory, it seemed as if the streets of Timișoara became like traps and the wind picked up and seemed to say to the fairy "you will never leave here".

His heart pounding with excitement, Ariam squeezed the fairy's hand and whispered encouragingly:

- Don't be afraid, Zephyra, we'll find a way to get you home.

At one point, right at a crossroads, a black cat cut them off. Its eyes glowed in the night like two mysterious candles. The kitten began to purr and talk, which Ariam found both amazing and delightful:

- Timisoara's roads are in a mess because the city won't let Zephyra go. But there is a secret way... you must find the hidden star! Only it can open the gate to the magical world.

Then Ariam remembered the paving star in Union Square. It's a good thing that when she's walking through the city, she's also paying attention to her feet! As if in flight, she headed towards the Square, the magic star hidden in the very heart of the city. With courage and perseverance, she overcame the dangers and made her way with the little fairy to the gate between the two worlds. She sat down in the middle of the square and seemed to enter a fairytale world. Here Zephyra bade farewell to Ariam thanking him for his courage and loyalty.

Returning home, Ariam knew that his meeting with Zephyra would never be forgotten. On starry nights, Ariam thought of the fairy and the wonders he had discovered with her. Every time she passed through the Union Square she felt like she was at the theater, ready to enter a fairy-tale world where characters and scenery could come to life under the mysterious moonlight.

For Ariam, Timisoara has become a city full of mystery, where every day can bring you new enchanting stories and make the city seem like a magical world full of enigmas.

Artwork by Muntean Bianca, student in class VIII B of General School No 19 "Avram Iancu" and exposed to UPT Library within the exhibition "Timisoara's Stories - A Visual Journey through Timisoara" - within the Creative Schools Project - Timisoara's Stories - a continuation of the Spotlight Heritage Timisoara project, part of the cultural program of the Timisoara Cultural Capital 2023 - project that brought together over 1600 children and teenagers and more than 60 teachers from Timisoara's schools, in over 50 interactive activities.

Artwork by Amalia Rusu, 9th grade C student "Grigore Moisil" Theoretical High School in Timișoara and exposed to UPT Library within the exhibition "Timisoara's Stories - A visual journey through Timisoara" - within the Project Creative Schools - Timisoara Stories - a continuation of the Spotlight Heritage Timisoara project, part of the cultural program of Timisoara Cultural Capital 2023 - project that brought together over 1600 children and teenagers and more than 60 teachers from Timisoara's schools, in over 50 interactive activities.

Artwork by Dumitrana Ranela, 9th grade student "Grigore Moisil" Theoretical High School in Timișoara and exposed to UPT Library within the exhibition "Timisoara's Stories - A visual journey through Timisoara" - within the Project Creative Schools - Timisoara Stories - a continuation of the Spotlight Heritage Timisoara project, part of the cultural program of Timisoara Cultural Capital 2023 - project that brought together over 1600 children and teenagers and more than 60 teachers from Timisoara's schools, in over 50 interactive activities.

Artwork by Tania Tomici, student in 9th grade "Grigore Moisil" Theoretical High School in Timișoara and exposed to UPT Library within the exhibition "Timisoara's Stories - A visual journey through Timisoara" - within the Project Creative Schools - Timisoara Stories - a continuation of the Spotlight Heritage Timisoara project, part of the cultural program of Timisoara Cultural Capital 2023 - project that brought together over 1600 children and teenagers and more than 60 teachers from Timisoara's schools, in over 50 interactive activities.

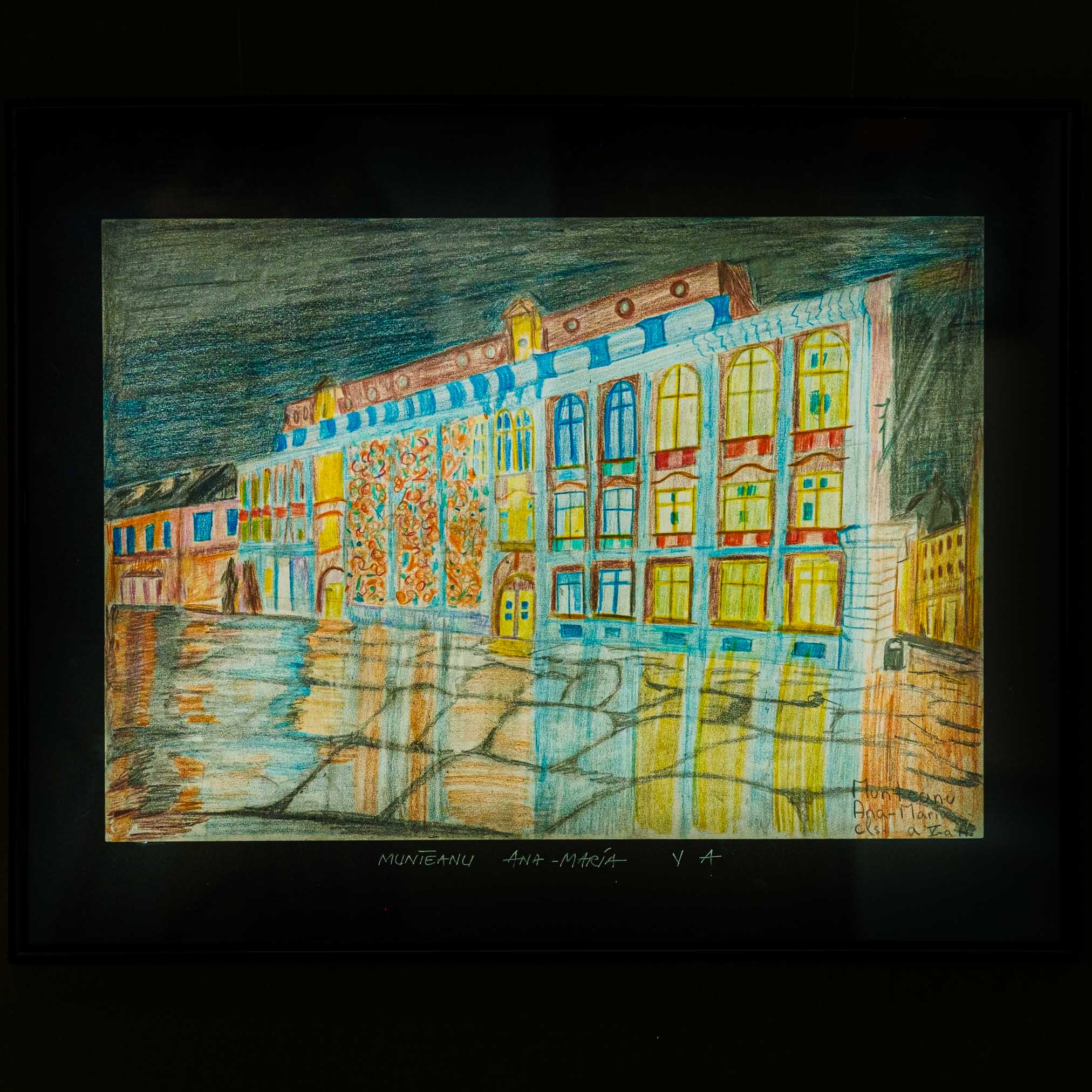

Work by Ana Maria Munteanu, 5th grade A student General School No 19 "Avram Iancu" and exposed to UPT Library within the exhibition "Timisoara's Stories - A Visual Journey through Timisoara" - within the Creative Schools Project - Timisoara's Stories - a continuation of the Spotlight Heritage Timisoara project, part of the cultural program of the Timisoara Cultural Capital 2023 - project that brought together over 1600 children and teenagers and more than 60 teachers from Timisoara's schools, in over 50 interactive activities.

Artwork by Anais-Maria Anderca, student in 6th grade General School No 19 "Avram Iancu" and exposed to UPT Library within the exhibition "Timisoara's Stories - A Visual Journey through Timisoara" - within the Creative Schools Project - Timisoara's Stories - a continuation of the Spotlight Heritage Timisoara project, part of the cultural program of the Timisoara Cultural Capital 2023 - project that brought together over 1600 children and teenagers and more than 60 teachers from Timisoara's schools, in over 50 interactive activities.

Artwork by Vlad Popovici, 5th grade A student General School No 19 "Avram Iancu" and exposed to UPT Library within the exhibition "Timisoara's Stories - A Visual Journey through Timisoara" - within the Creative Schools Project - Timisoara's Stories - a continuation of the Spotlight Heritage Timisoara project, part of the cultural program of the Timisoara Cultural Capital 2023 - project that brought together over 1600 children and teenagers and more than 60 teachers from Timisoara's schools, in over 50 interactive activities.