Mihai Viteazu Boulevard

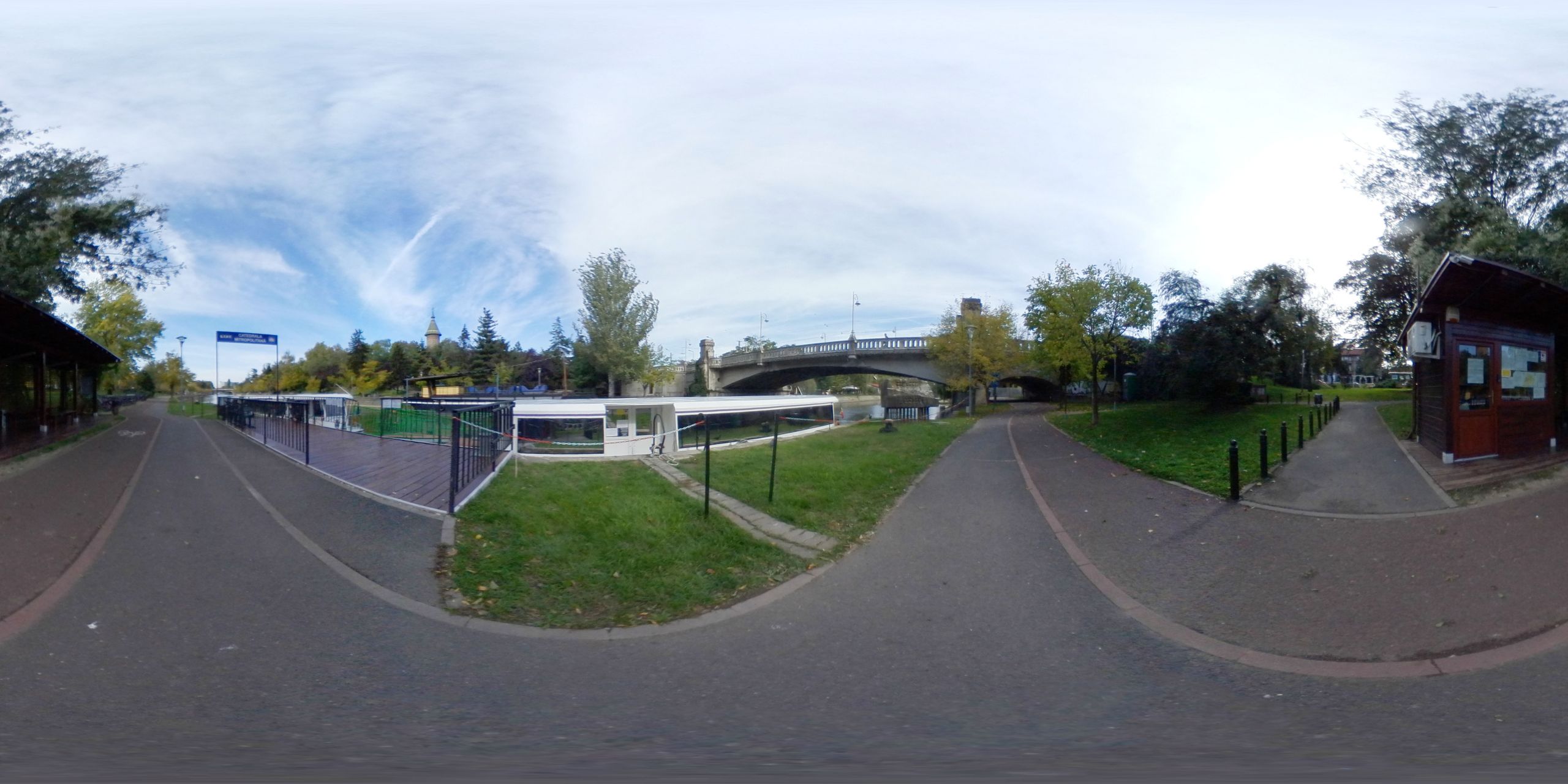

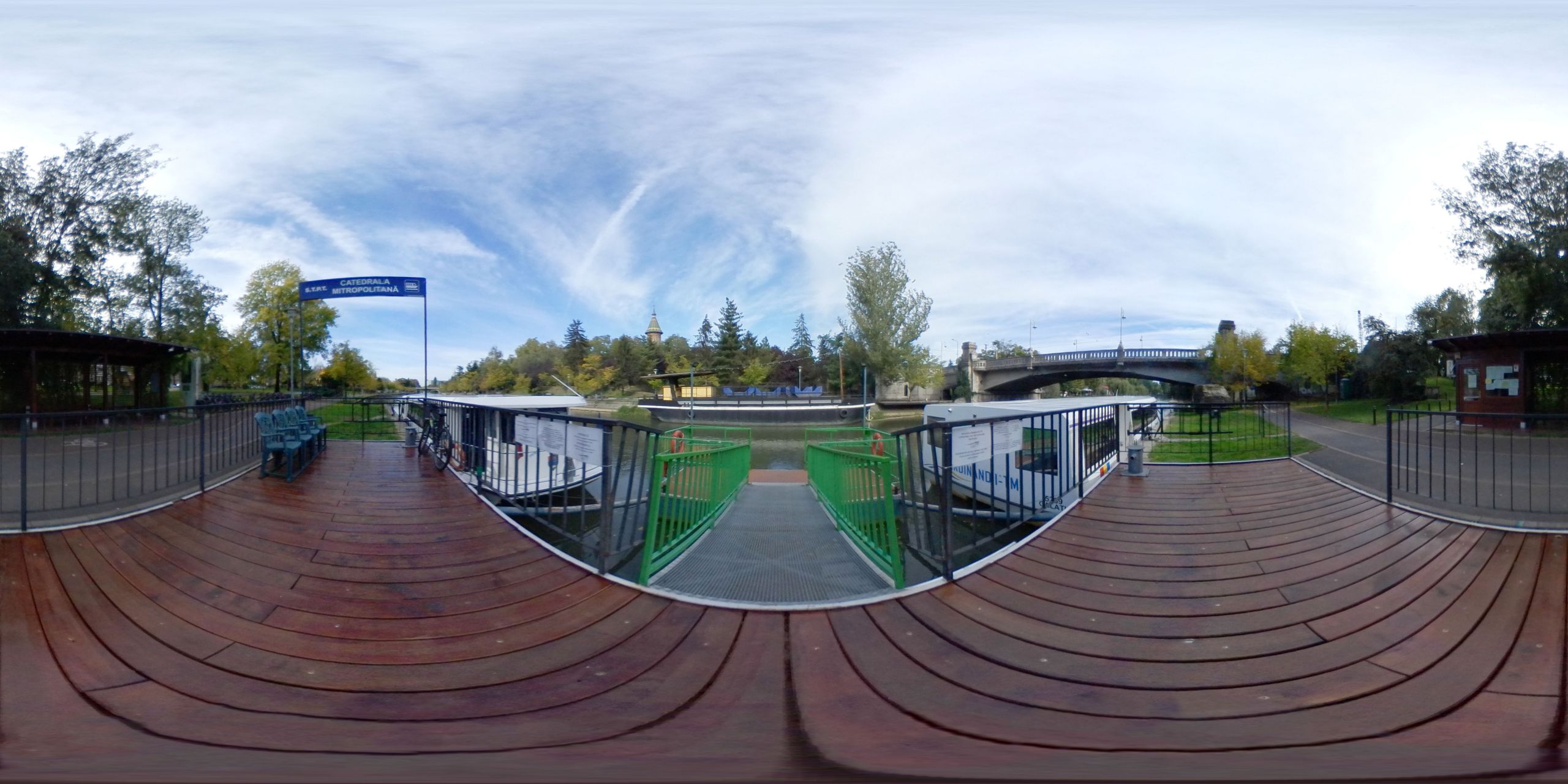

The Metropolitan Bishop Andrei Șaguna bridge, formerly called the Bishops' Bridge, was put into use in 1913.

Listen to the audio version.

Ever since the time before the revolution of 1848/1849, a wooden bridge was placed here, which was repeatedly strengthened and repaired. In 1911, within a larger program of the Timișoara municipality for the arrangement of new bridges, the decision was made to replace the old wooden bridge with a modern bridge.

The architect Gerster Kálman from Budapest was contacted to carry out the architectural projects of the bridge, the technical design of the bridge being the responsibility of Lád Karoly, an engineer at the engineering office in the city on the Bega. The projected width of the path on the bridge was 10 meters, a value considered very high for the needs of those times. With the exception of a few syncopes, due to the often unfavorable weather conditions in 1912, the work went well, so that from 24 November 1913 the bridge was put into use for vehicular traffic, after it had been opened, shortly before, for pedestrian traffic. Together with the opening of the new bridge began the dismantling of the old bridge, the last wooden bridge and at the same time one of the oldest in Timișoara.

According to the initial intentions, the bridge was to be inspired by the famous Charles Bridge in Prague and have two statues at each end, representing four prominent bishops of the Roman Catholic diocese of Cenad: St. Gerhard, the first bishop of the Cenadian Diocese, Joseph Lonovics, Alexandru Dessewffy, and Ladislau Koszeghy.

However, the outbreak of the First World War thwarted the realization of this plan. There was an intention to widen the bridge in the second half of the twentieth century, but this plan did not materialize. The bridge, which - according to the expertise of the bridges over the Bega in the 1970s - had the best viability and resistance, continues to serve its original purpose today.

Bibliography:

Jancsó Árpád, The History of Bridges in Timișoara, Mirton Publishing House, Timișoara, 2001.

Listen to the audio version.

Pia Brînzeu, Family Journal, Manuscript

Stop 16: The bishops’ bridge / The Mitropolit Andrei Şaguna bridge

April 1, 2008. Like in an April’s fool prank, I woke up obsessed with the letter K. I discovered that, if you wanted to, you could connect everything under the sign of a single letter. No matter which one. K is less common for Romanians, but that’s the very reason why it is challenging enough to push you towards a labyrinthine, undulating, hard to define zone. A zone that is somehow lost among the fogs of other languages. I let myself be tempted, knowing it feels nice, from time to time, to not be sure of what you are saying, to not clearly delimit concepts, and to open yourself through one such fuzzy concept to a risky or even damaging adventure. I was hoping to discover something new within this territory, to run into a poem of the unknown where you rather feel than think. In the worst case, I told myself, the mystery of the letter K will throw me into the geography of Central Europe and will make me evolve like William Blake’s “mental traveller”: the search will make me become less and less knowledgeable and, thus, the subject of a perpetual rejuvenation.

However, the result of my thoughts was, unfortunately, clear and well defined geographically. I didn’t know how to get lost in the fogs and I remained sheltered only in my grandparents’ two towns: Jimbolia and Lugoj. There doesn’t seem to exist anything for me beyond them. Unlike the Romanian Lugoj, Jimbolia has more names - Hatzfeld/Zsombolya/Žombolia – and it reminds me of the streets of my Timișoara childhood, where I would go for walks with Grandmother Netti or with Mother, both used to talking with people in three languages and tolerantly accepting different opinions, ethnicities, and religions. In Jimbolia, the letter K relates to my great grandfather, Karl Diel, and to Kaba Gabor, the mayor who has helped me to set up a memorial house for my great-grandfather. In the same way in which the troublesome letter can throw you into Central Europe, the museum has been conceived to illustrate the way in which a Central European family used to live in Jimbolia in the previous century. That’s why I have placed in showcases my great-grandfather’s business cards in four languages, my mother’s school certificates, as she went to German, Hungarian, and Romanian schools, as well as the photographs in which she is wearing Tyrolese, Swabian, Hungarian, and Romanian costumes. I have chosen birth, baptism or death certificates in several languages, and the statements of Hungarian or Romanian nationality belonging to Germans who, once moved to these lands, had to shift their identity from one ethnicity to another according to how the borders moved over Jimbolia. They would do it with serenity and free of any vanity, passing from Karl to Károly or Carol as if it wasn’t about them, it was about an area that needed to be mapped in a modest and friendly way. And so the first letter of the name could be replaced with any other, without any problem.

How did the letter K get to Lugoj, though? It’s quite simple. Kurtág Gyorgy was invited there yesterday, to receive the title of honorary citizen of the town he was born in, but also the title of Doctor Honoris Causa of the National University of Music from Bucharest. Well-known as a composer in Hungary and France due to works which modernized and simplified the musical language, while also connecting him to literature, Kurtág is also a Central European citizen whose life and work link Eastern to Western Europe. The official festivities in Lugoj also included a touching moment for me, when he delivered to me the composition entitled Carol-ballad, op. 46, dedicated to the memory of my uncle, Felician Brînzeu, who had been Kurtág’s Romanian language teacher at the “Coriolan Brediceanu” high school. He confessed to me that this uncle had impressed him so much as a teacher, through his love for the Romanian language and for music, that he used him as a role model for the rest of his life. That’s how he has succeeded in never growing old. By loving art and by gifting to others parts of his sensibility, he always slipped back to his youth and could rightfully be placed among Kafka, Kerényi, Kiš, Klimt, Koestler, Kokoschka, Konrád, Kundera and Kusniewicz. Those who bear the name of Karl could also be placed there. However, only the first letter of the first name, all by itself, is nowhere near enough...

Timisoara, a fairytale place

by Matei Popa, 7th grade

"Grigore Moisil" Theoretical High School Timișoara

In the pages of history, Timisoara writes its own story,

With words that remain vivid and meaningful.

On its cobbled streets walk the shadows of the past,

And the echoes of heroes can be heard in every corner and in every stone.

On the outskirts of the city, in chestnut and acacia woods,

They say there are still sighs of love and unfulfilled longings.

Love stories grow under the starry sky on the banks of the Bega,

And old legends handed down from generation to generation, like the wind caressing the leaves of old trees.

In Union Square, the heart of the city beats faster,

Among buildings and fountains shimmering in the moonlight.

Political meetings and plots take place here,

And they say that every stone holds a secret waiting to be revealed.

The narrow streets of the Citadel hide mysteries and mysteries,

And every corner has a story waiting to be discovered.

With every step, you feel like you're stepping into another era,

And you can hear the sighs of yesteryear and the laughter of children running through the old streets.

Revolutionary stories and ideas are born in bohemian cafés,

Where poets and intellectuals find refuge in words and thoughts.

At a coffee table or under gas lamps,

It sparks heated discussions and plans that will change the course of history.

On the outskirts of the city, in suburbs and suburban neighborhoods,

Stories of life and struggle for survival emerge.

Every house and courtyard has a story,

And everyone is proud of their ancestral traditions and customs.

On the border between past and present, Timisoara is building its future,

With confidence and determination, overcoming obstacles as they arise.

Every day, a new page is written in the book of his destiny,

And each inhabitant adds their personal story to the city's rich tapestry.

In the Central Park, under the shade of ancient trees,

Stories of friendship and love, joy and sadness unfold.

Every bench and alley hides memories and stories,

And every visitor adds a new chapter to the park's beautiful book.

On the border between reality and fantasy, Timisoara becomes a magical place,

Where fabulous characters meet mythical creatures.

Fairytale scenes unfold in the narrow streets and crowded squares,

And every inhabitant becomes part of a story that transcends the boundaries of reality.

At the crossroads of cultures and traditions, Timisoara becomes a melting pot of diversity,

Where customs and rituals from all corners of the world intertwine.

Every festival and holiday celebrates unity in diversity,

And everyone feels proud to be part of this multicultural city.

On the outskirts and in the heart of the city, nature shows its splendor,

In gardens and parks that stretch on forever.

Every tree and flower tells its story,

And every river and lake becomes a testament to the beauty of the city.

Through the passing years and the changes that come with them,

Timisoara remains a place full of charm and mystery.

In the hearts of the inhabitants and in their ancestral memories,

It keeps alive the flame that ignites the spirit of the city and gives it life.

At the end of the journey through Timișoara's Stories,

I turn wistfully to the city in front of me.

With a heart full of memories and a soul enriched by experiences,

I am slowly drifting away from this place of stories and magic.

With the promise that I will come back one day to discover new stories,

I leave with a light step and a smile on my lips, because I know that this city,

With all its stories, it will always be alive and vibrant,

A place where history intertwines with the present, and the future always shines in the distance.

At the crossroads, I reach up to the sky and say one last thought,

Thanking Timisoara for its beauty and wonderful stories.

With a heart full of gratitude and the desire to return,

I am leaving for new adventures, but with the promise that the memories of Timisoara will always remain alive in my soul.