The building was built between 1872 and 1875 in the intra muros area of the fortress, according to the plans of the architects Ferdinand Fellner junior and Hermann Helmer, in an eclectic historical style.

Listen to the audio version.

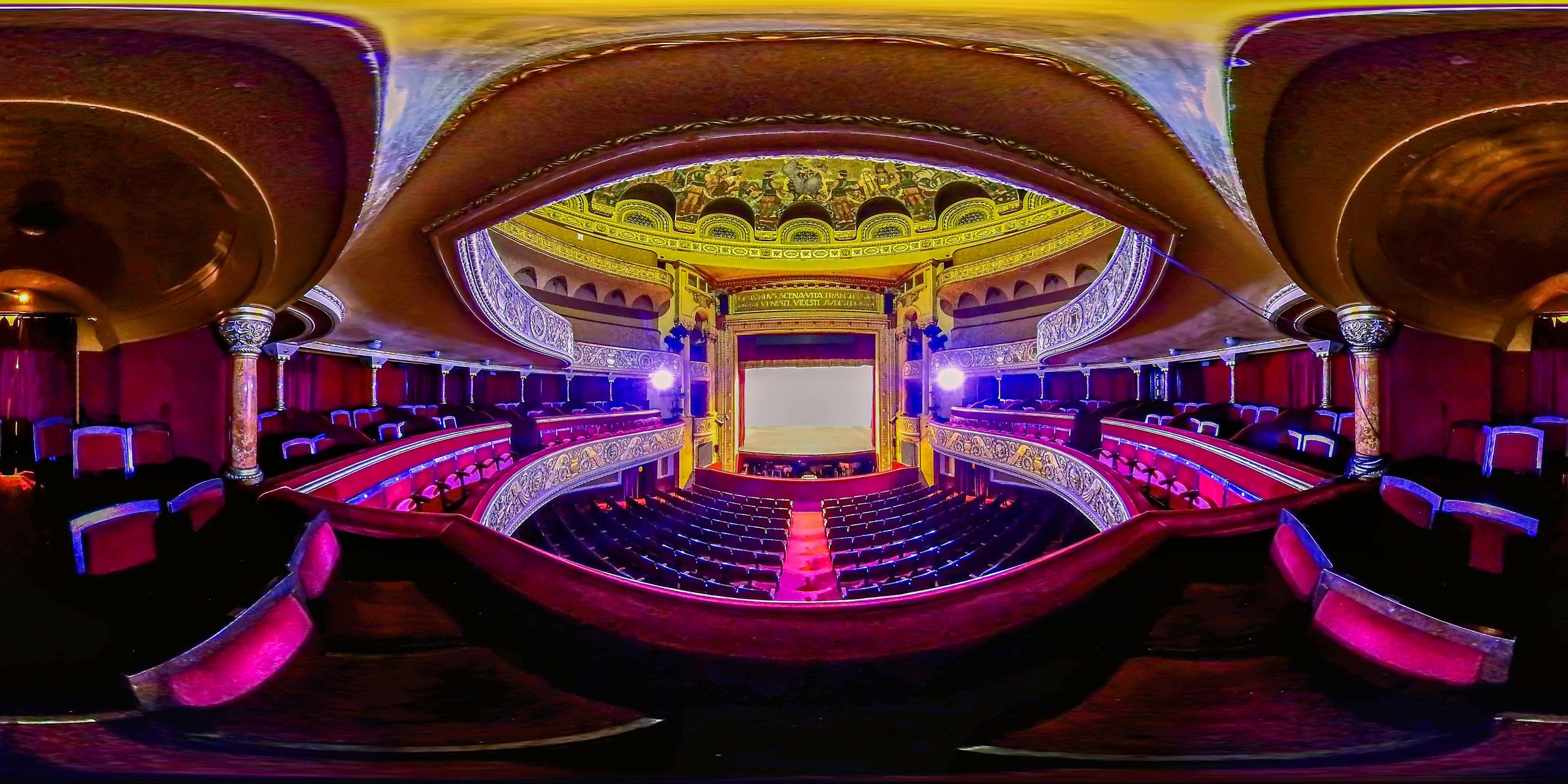

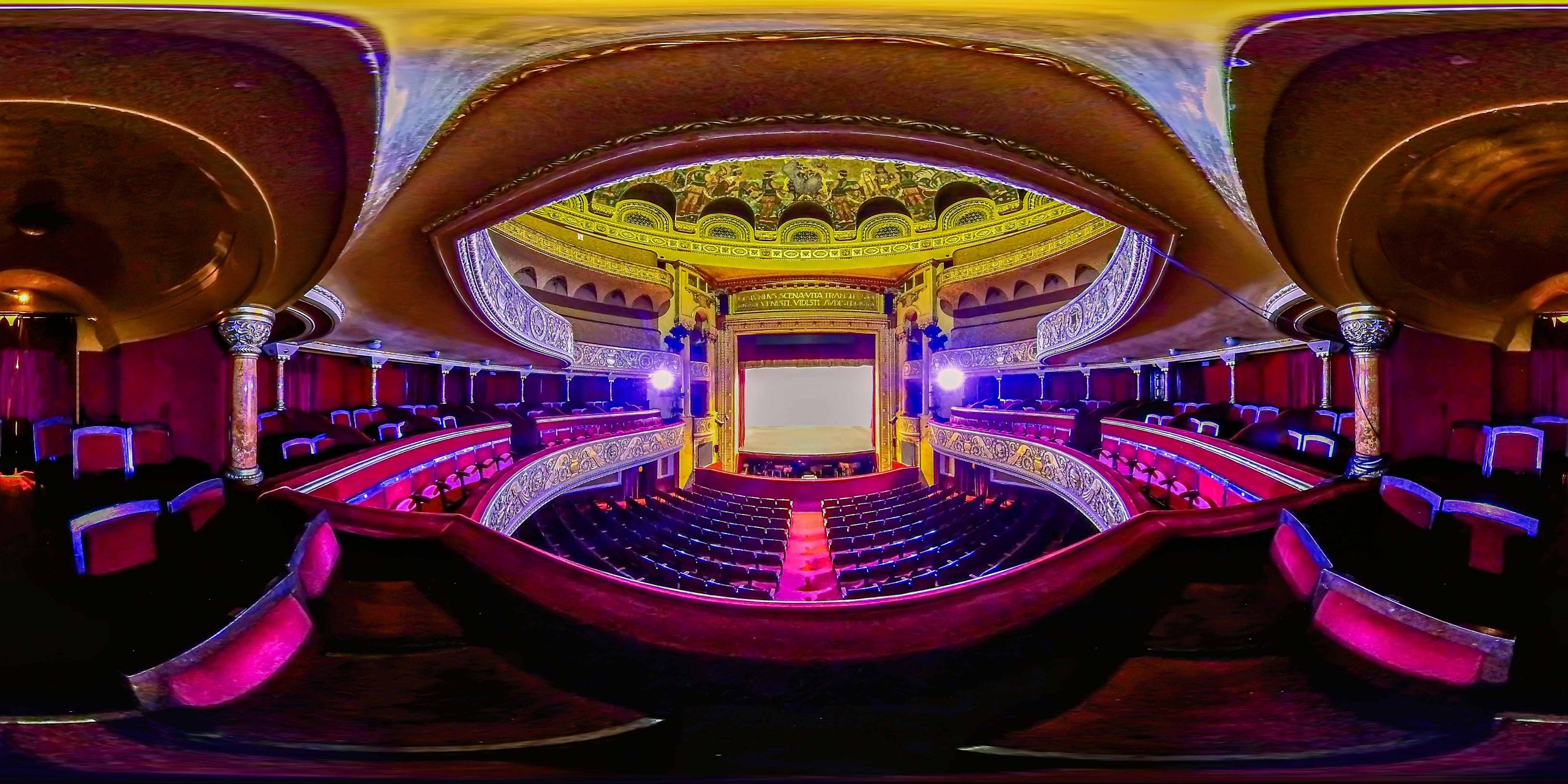

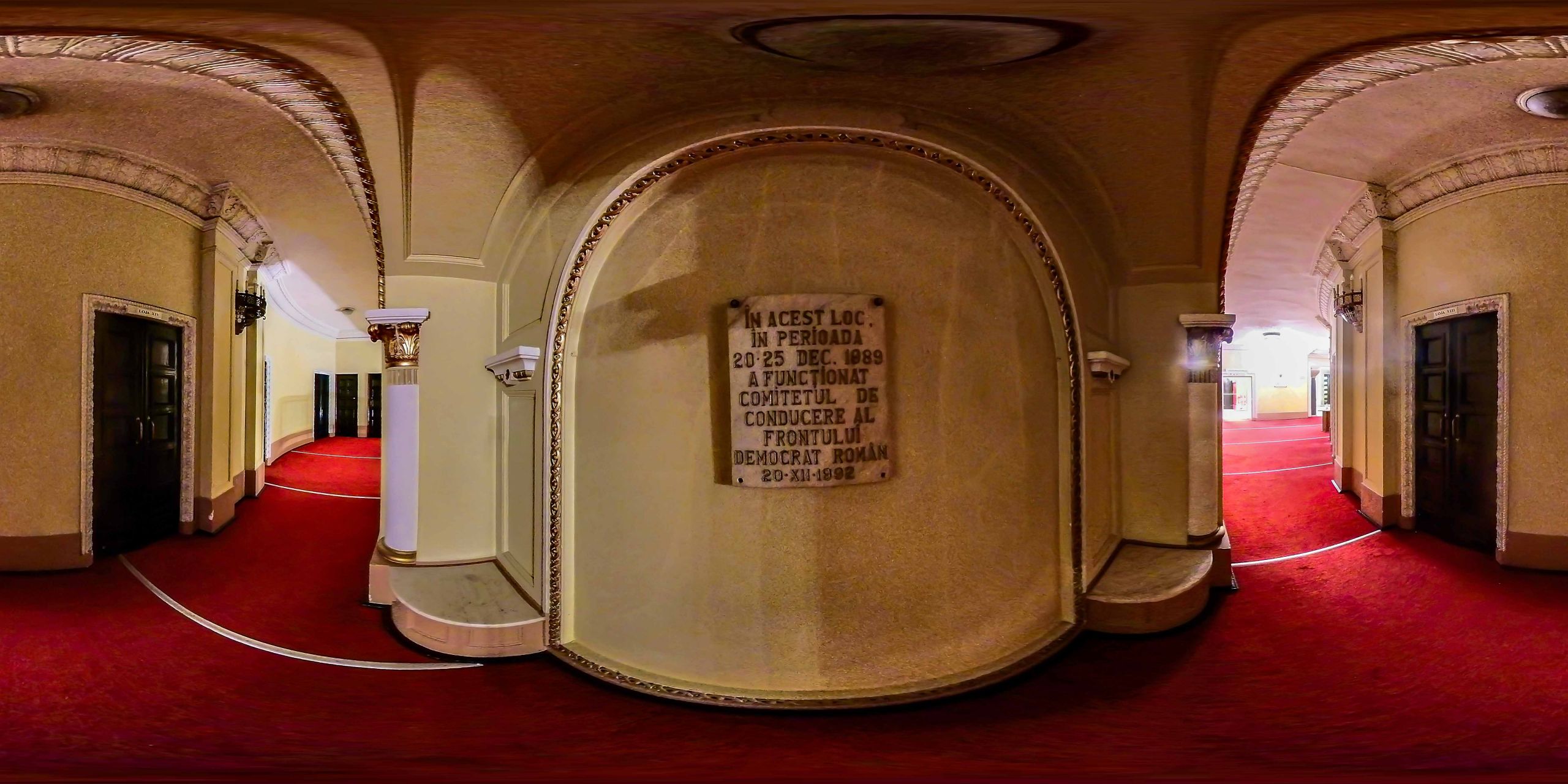

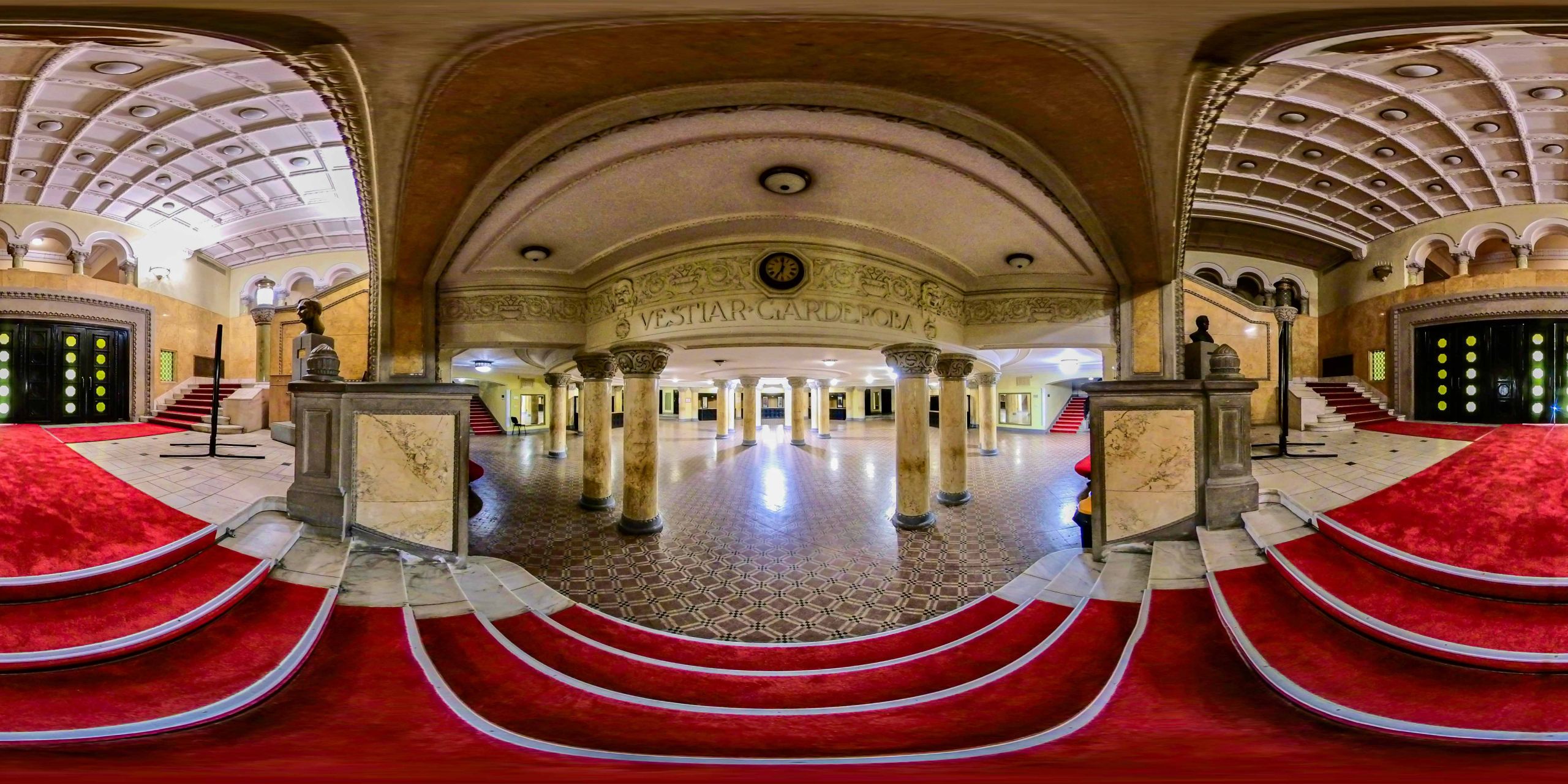

From the balcony of the Opera House, Timișoara was proclaimed the first free city in Romania on December 20, 1989. The Palace of Culture was built in the northern part of the square, a building that houses several prestigious cultural institutions: the National Opera, the Mihai Eminescu National Theater, the Hungarian State Theater Csiky Gergely and the German State Theater, along with the Workshop/Exhibition of Timișoara City Hall Urbanism, Timișoara City Hall Tourist Information Center and many commercial companies. The so-called "Palace of Culture" dates back to the 1930s, when this building housed the theater, the Banat Museum, the Academy of Fine Arts and the Banat-Crișana Social Institute. The theater was built between 1872 and 1875 according to the plans of junior architects Ferdinand Fellner and Hermann Helmer, in an eclectic historical style. After the fire of April 30, 1880, the theater was bought by the city from the joint-stock company that owns the building, with the amount of 150.000 florins, investing 120.000 florins for the reconstruction of the theater between 1880-1882. The building suffered a strong fire on October 31, 1920, the interior being completely rebuilt between 1923 and 1928 according to the plans of the architect Duiliu Marcu in neo-Romanian style. In 1934, the same architect designed a new theater façade, completed in 1936, as a perspective for Victoriei Square. The year 2003 marks the return to the original architecture of the sides of the main façade (architect Marcela Tietz). Victoriei Square, formerly Opera Square, is one of the central squares of Timișoara, with a very important historical significance for the events of December 1989: from the balcony of the Opera House, Timișoara was proclaimed the first free city in Romania on December 20, 1989. In the northern part of the square, the Palace of Culture was built - a building that houses several prestigious cultural institutions: the National Opera, the Mihai Eminescu National Theater, the Hungarian State Theater Csiky Gergely and the German State Theater, along with the Workshop/Exhibition Urbanism of Timișoara City Hall, Tourist Infocenter of Timișoara City Hall and commercial companies. The name "Palace of Culture" dates back to the 1930s, when this building housed the theater, the Banat Museum, the Academy of Fine Arts and the Banat-Crișana Social Institute. The theater was built between 1872 and 1875 in the inner wall of the fortress, according to the plans of junior architects Ferdinand Fellner and Hermann Helmer, in an eclectic historical style. During his visit on May 7, 1872, King Ferenc József approved the theater to bear his name. The performance hall had 900 seats, but in the building also operated the Kronprinz Rudolf hotel and the Redoute dance and festivities hall. In the wing of the building on Alba Iulia Street you could find a cafe, a reading room, a bowling alley and a club - where you could play cards. The cost of the building was 1,440,000 forints. The theater building was inaugurated on September 22, 1875 with the play Women's Domination by Ede Szigligeti. After the fire on April 30, 1880, the theater was bought from the joint stock company that owns the building, by the city, with the amount of 150,000 florins - further investing 120,000 florins for the reconstruction of the theater between 1880-1882. In 1890, the building underwent a restoration process, by restoring the interior furniture by the carpenter Ferenc Gungl, gilding the performance hall by Jenő Sprang, reconditioning the sculptures by Alajos Heine, changing the heating system, arranging new toilets, purchasing an electric motor for the iron curtain (a firewall between the stage and the performance hall), the installation of two new water basins and the reparation of the roof. Architecturally significant for this stage is the entrance from the ground floor, with three openings finished in the arch in the center. After the Great Union, the first show in Romanian language on the stage of the theater took place on August 7, 1919, with the play Institutorii by Otto Ernst, played by actors from Craiova. The building suffered a strong fire on October 31, 1920, the interior being completely rebuilt between 1923 and 1928, according to the plans of the architect Duiliu Marcu in neo-Romanian style with Byzantine ornaments and Art Deco. On November 12, 1923, King Ferdinand of Romania laid the foundation stone for the reconstruction of the theater, and it was later reopened as the Communal Theater on January 15, 1928 with the show Red Rose by Zaharia Bârsan. In 1934, the same architect designed a new facade for the theater - completed in 1936, as a perspective for Victoriei Square, the works being coordinated by the architect Edmond Stanzel and the entrepreneur architect August Schmiedigen (Bucharest). The new facade dominated by a monumental triumphal arch is a balanced perspective for the wide esplanade of Victoria Square. The year 2003 marks the return to the original architecture of the sides of the main facade (architect Marcela Tietz).

Bibliography:

- Mihai Opriș, Mihai Botescu, Historical Architecture from Timișoara, Tempus Publishing House, Timișoara, 2014

- Josef Geml, The old Timișoara in the last half of the century 1870-1920, Cosmopolitan Art Publishing House, Timișoara, 2016.

The National Theater and Opera House

Listen to the audio version.

Robert Șerban

whenever I pass by the theater

I remember the balcony scene

when those upstairs

and those downstairs

were both so much in love

with freedom

waiting for it to turn

to eternity

June 2022

“He reached the great Central Square of the city. Only pigeons used to fly around here once. Now the vast area was packed with people. Up in a balcony of the National Theaterbuilding, a hustling crowd, speakers taking turns at a microphone. They were occasional speakers, each saying whatever was on their mind. Some were listened to with the utmost attention, getting a round of applause after every sentence, others were talking without any applause, leaving quickly, someone else taking their place. From the sides, some tanks, or whatever they may have been, guarded the unsettled crowd and those speaking from the balcony.” (Ion Arieșanu, The Best Die First, Timișoara, Amarcord, 1998, p. 224)

“He walked along the boulevards, the streets, the squares, went inside the churches, walked along the passageways, reached the park alleys, the riverbank, and kept walking and walking... Until he realized he was falling off his feet. And that it was evening again. The hustle had faded away. In the National Theatre Square, in front of the Cathedralas well as on the main boulevards. After the euphoria of the day, after the hours of bliss, the alarming sound of gunfire and machine guns could be heard again here and there, coming from unknown parts of the city. Again, tanks in the streets. Again, few lights. Again, hurried passers-by sneaking past walls. What was going on, though? He wondered sitting on a bench, looking around the deserted park, as his weary body started to cool from the evening icy winter wind creeping through the trees. What’s going on, for God’s sake? Isn’t it over, all the madness?” (Ion Arieșanu, The Best Die First, Timișoara, Amarcord, 1998, p. 247-248)

Francisca Schultz (b. 1950)

(...) As a child, my parents, although they were simple people, gave me an extraordinarily good education, in the sense that I did nine years of ballet at the Opera. I graduated from school, so I could have become a ballerina. I had colleagues who remained employed as ballerinas at the Opera. I even had roles in performances alongside the Opera's employed ballerinas. However, I was always a prize winner at school. And my father said to me: "You won't make a job out of this!" He came at night - at eleven o'clock he left his shift at work, at 23:30 he was already standing behind me backstage, waiting for me until I left the stage to take me home. He could see the dancers, especially the soloists, almost spitting their lungs out, excuse the expression, between the dances. My father said: "I won't let you do that kind of work." Women retired at forty, men at forty-five and they were already wrecks. He said, "Why destroy your health? (...) just keep going to school".

At the opera, at one point, I was sixteen years old, a coach came to visit us from Bucharest, she was a national champion in rhythmic gymnastics, the one with “the objects”. In school, I also did about three years of apparatus gymnastics. The sports teacher would sometimes let me hold the lessons in her place with my colleagues - on the floor, on the beam, on the parallel bars, on all kinds of things like that. I was always active, when there was a contest or any celebrations, at sports, at all the schools I went to, I always participated and got prizes.

Ok, so… that coach from Bucharest came to the opera. And she chose six girls. She made the first rhythmic gymnastics team of Timişoara, and we participated in the first national competition of this kind. I also participated in the Balkans at one point. In the meantime I had become a student. I had practiced gymnastics for four years. One could very easily switch from ballet. We had to do the craftsmanship ourselves, because we had the base, the ballet. And that's what you need for rhythmic gymnastics. In the second year of college, the Polytechnic demanded a lot from me and I gave up on everything. This is my great pain. For years and years I couldn't watch a ballet performance like the rest of the world. I was sobbing and had to go outside. (...) For decades, at night, I dreamed of dancing and even today, I can say that I still know every move of everyone in Swan Lake , for example. That was my whole childhood, in the Opera. Then I also played the piano at the pioneers' palace, I did a theater circle, a painting circle, everything possible. I did everything. (...)

Francisca Schultz (b. 1950) interviewed by Onica Adrian in Timisoara in 2017 (interview published fully in Smaranda Vultur (coord.) Germans from Banat through their stories, second edition revised and added, 2018. Polirom, Iasi)

Viorica Adriana Reus

[...]

(How was it with the operetta?) After we came to the refuge ( from Bucovina n. n.), the Opera from Cluj came as well, and the Conservatory from Cernăuţi, which turned into the Academy of Music and Dramatic Arts, here in Timisoara. So I had no financial possibility. We were all very poor, so the Operetta Lyric Theater was founded. Different people came here, just like today, to make "shops", different people came to lead us. The first one was a pharmacist, called Octavian Hrabal. All cultural activity started because of him. He stayed for two months, collected the money from the shows and quit. The second one came, an innkeeper, his name was Savu. He also had a bit of a voice, he was a bit of a tenor. He also took the money and left. Then we got a swine herd. (Where was the headquarters?) We didn't have an actual headquarters. We held rehearsals at the Conservatory, on Ungureanu Street. The performances were held at the Opera House. We didn't have decorations there, we got them from the City Hall. The town hall, once upon a time, in 1800 or so, had a municipal theater that also had sets and costumes and we took what we needed from there. We had three premieres, "Polish blood", "House with three girls" and one more.

It was then Cornel Trăilescu who was then a student at the Conservatory. Now he is the first conductor at the Bucharest Opera. He took the six of us. There was a lady and a gentleman, who during the war made a French magazine around the premises. His name was Stănescu, and her name was Eviţchi, a very beautiful voice. In the beginning, we were just a bunch of people with a big soul. I had my role, I was the child of the street, nobody's child and I sold newspapers. The other two were tapping and singing. They were the main actors. Trăilescu was with the music, he played the piano and made our songs. After stabilization, we managed to give performances in a commune, Pecica, but they told us that they could not receive us because they had no money. The ticket was 27 lei. Then I came up with a great idea, the first row should give us a chicken, the second row eggs and flour, everyone would bring a gift from home, instead of paying for the ticket. It was very difficult. Then the Opera was established, with the decree of King Mihai and with the presidency of Minister Groza and with Aca de Barbu who was a soloist, an emeritus artist, and a director. Rehearsals have begun. They slept in cabins, on straws. They had nowhere to eat. There was only one oil lamp and food was cooked on it - boiled potatoes, beans. This was done in the corridor, at the booths and all that smell came into the hall, so everyone always knew what the artists were eating.

One time, a soloist told me to bring him a fork and a spoon from home. The artists were eating at the station, in the basement, where the mite canteen was. There was a long wooden table on which the metal plates were nailed. From these plates, there was a spoon on a chain and the cook came with a vailing and a cloth and washed the plates, then the spoons, from one to the other. On the day I went there, they had tomato soup on the menu, which was only slightly reddened, and some macaroni thrown in there. After he came with the cloth, the second course was macaroni with marmalade. And that's where the artists were eating. There was great mourning… great mourning.

The director, Aca de Barbu, was amazing. In order to help the artists, there was a law, if someone saved the show, when someone else was sick, they would receive 500 lei, which was almost half a leaf. The headmistress once told the prop cook, the one who takes care of the details, to tell his wife to make a big bowl of potato dumplings, with cheese and well buttered. This is in the play "House with three girls". In the role, Kupelwieser was a great philosopher. I was Schani, picolo, and I had to help at that table. In the play it said, "Kupelwieser, isn't that chop coming anymore?" and he says, "It's coming, it's coming, it's hot."

I went ahead of him, took the bowl, but there were some nails under the stage carpet and I tripped over them and the bowl fell and the dumplings fell all over the stage.

All the soloists were prepared with plates and forks, because they had something to eat that evening, and they said to me: "What have you done Schani, you spilled our dumplings!" I was very ashamed and sorry that they lost a dinner like that. I collected the dumplings and went out.

Master Georgescu did not let you change a word in the role you had. My text was, on the way out: "Bon appetite!" but why say "Bon appetite" when all the food was on the floor. They had to take the line from me and say: "Hooray, good appetite, let's eat and drink!" I was sitting backstage and watching what they were doing on stage. Two were left on stage, the tenor and the soprano, Hamerl and Schubert. She asked Schubert, who was a composer, to give her singing lessons. She was one of the three daughters of a large bottle manufacturer. She was sitting with an umbrella, and when she was about to leave, she opened the umbrella, and there was a dumpling on top of it. Everyone laughed so hard at this. In the tram and everywhere, until I got home, they told me: "Be careful not to lose the dumplings like Schani did."

I was about 14-15 years old back then. These were the adventures we had at the Opera House. It was very difficult.

Viorica Reus (n. ) interviewed by by Adrian Onica in February and March 2002 in Timişoara, fully published in Bessarabians and Bukovinians in Banat. Life stories ( Smaranda Vultur, Adrian Onica editors), Marineasa 2010, Brumar 2011.

I went to the Theater because I liked it a lot. I went to the Opera every Sunday. I went, I liked it...I saw a lot. (Were the actors from Timişoara?) They were from Timişoara, from here, a very good team. "The Prince of the Gypsies", it was so beautiful, in Romanian language!

Maria Zettel (b. 1913) Interviewed by Roxana Pătraşcu Onica in 1999 in Timişoara (Third European Archive, BCUT)

Listen to the audio version.

The Opera and Theatre Building means more to me than what it is historically: a symbol of change. My story begins in my childhood, when my father, a composer, and I used to visit the building, which was one of my second homes. Over time, I began to unravel more and more of the rooms of the opera: from the preparation and rehearsal rooms, to the emotions behind the scenes, to those of the artistic moment. But it's not just the inside that I'm very familiar with, but the outside as well. The outside, however, knows me as a different kind of performer. So, for me, the inside of the Opera is the formal, classical world of theatre and opera that I have loved since I started remembering things from my childhood, but the outside knows me a little less formally, as a fire-juggling performer, a man of historical re-enactment and so on. So, symbol of change, duality, and different memories for everyone.

Raluca Goia, UPT Student, 2023