Status Quo Synagogue, 1 I.L. Caragiale Street

The new synagogue in Fabric was built by the Status Quo mosaic community in 1899 in the Moorish style and was originally located on the bank of an arm of the Bega canal, which was later covered into a street.

Listen to the audio version.

The new Synagogue from Fabric was built by the Status Quo mosaic community in 1899. This imposing building, with a high dome and two towers, was built in the Moorish style and was originally located on the bank of an arm of the Bega canal, which was later covered and became a street. The Splash Kunz provided the natural boundary of the Factory to the non-building esplanade of the Cetate neighborhood, giving the volume excellent visibility, following the Archduke's House (1868) and the Josef Kunz Palace (1892), two buildings that provided the monumental gate of the neighborhood.

The religious building, designed by architect Leopold Baumhornfrom Budapest, cost 162,000 crowns. After a first presentation of the project, Temesvarer Zeitung headlined on November 28, 1896: “The project is fabulous ! (...) the building will be imposing (...) and will be one of the most special architectural ornaments of the city of Timişoara ”. The success of the presentation mobilized the Jewish community in Fabric and, in a short time, most of the funds were secured through collections and donations. The local authorities contributed 6,000 crowns, obtained following a tender organized for this purpose.

In addition to Amalia Freund, who donated half the value of the land needed for construction, Alexander Kohn, the sales representative and lawyer of the Kunz brick company, also played an important role in the Synagogue's construction committee. He also served as chairman of the committee.

On September 3, 1899, on the eve of the Jewish New Year, the inauguration festivities took place in the presence of the emblematic mayor of Timișoara, Dr. Karl Telbisz, and Rabbi Jakab Singer.

Bibliography:

Josef Geml, The old Timișoara in the last half of the century 1870-1920, Cosmopolitan Art Publishing House, Timișoara, 2016.

Getta Neumann, On the trail of Jewish Timisoara. More than a guideBrumar Publishing House, Timisoara, 2019.

I was born in the commune of Ceica 83 years ago, in January 1917. It was a Romanian village, only a few Hungarian families were on the edge of the village. And there was a large Jewish community. These are the first things of a Jewish community: the temple, the rabbi, the haham, and the teacher. (...)

After finishing the 4 primary classes, because we, as “am ha-sefer” as "people of the Book", we must strive to absorb as much as possible from the source of science, of knowledge, my parents sent me in Oradea where, at my uncle I found accommodation, I attended the first 3 classes of the Israeli Orthodox gymnasium that operated in Oradea. Then, in order to pass from the third grade to the fourth grade, it was an entrance exam that I also passed in Oradea. In the meantime, my parents moved from Ceica to Beiuş. In Beiuş there was a high school, not an ordinary high school, it is one of the high schools that brought fame to Transylvania. It was a Romanian high school called "Samuil Vulcan", which was founded in 1828… and then I continued my studies at this high school, a high schools famous to this day. All those from Beiuş, those who once graduated from high school in Beiuş meet again here in Timişoara every year at the "Ball of Bihoreni", when the current leaders of the high school in Beius, teachers from there and we meet, as a family, those who they have some connection with the city, those who were connected to the school and those who currently live in the town.After finishing the 4 primary classes, because we, as “am ha-sefer” as "people of the Book", we must strive to absorb as much as possible from the source of science, of knowledge, my parents sent me in Oradea where, at my uncle I found accommodation, I attended the first 3 classes of the Israeli Orthodox gymnasium that operated in Oradea. Then, in order to pass from the third grade to the fourth grade, it was an entrance exam that I also passed in Oradea. In the meantime, my parents moved from Ceica to Beiuş. In Beiuş there was a high school, not an ordinary high school, it is one of the high schools that brought fame to Transylvania. It was a Romanian high school called "Samuil Vulcan", which was founded in 1828… and then I continued my studies at this high school, a high schools famous to this day. All those from Beiuş, those who once graduated from high school in Beiuş meet again here in Timişoara every year at the "Ball of Bihoreni", when the current leaders of the high school in Beius, teachers from there and we meet, as a family, those who they have some connection with the city, those who were connected to the school and those who currently live in the town.

After graduating from high school, I attended the rabbinical seminary in Budapest, where, from the very beginning, it was stipulated that, in parallel, the one who is a seminarian, after the entrance exam by which he was accepted in that institute, should also be a university student. At that time, in Budapest you were forced to choose between ancient history and Semitic languages after four years of education. You had to do a dissertation. The title of my dissertation was "On the History of Creation," as presented in the Haggadah in a specific part of the Talmud. And before graduating from the seminar, you had to have the doctoral degree that the jury of 7 professors and the president granted you in a very festive setting. You introduce yourself to everyone and everyone says “Doktorrá avatom” (“Hungarian transcription”), they look at you, they accept you as a doctor.

(...) After finishing my studies - it was already in 1940 - I returned to the country, because from the first moment with this intention I went to study in Budapest - to practice in Romania. I also took an aptitude test in Bucharest, and from April 3, 1941, I was employed by the Jewish Community of Timisoara. In the beginning, I taught in two ways: 8 hours of religion a week, and at the same time I served as a rabbi at the temple in Fabric, because I had to replace Singer Iacob, who was for decades the first rabbi of the temple within the Jewish Community of Timisoara. At that time there were many Jewish schools: primary schools, high schools, boys 'high school, girls' high school, commercial high school.

It was a difficult time for me, because I had just arrived here on April 3rd, and on August 3rd the period of Antonescu's dictatorship came, when it was ordered that all the young people who had reached the age of 18 should gather on the ground from the Electric Arena, near the “Small Station” in Timişoara. I was also assigned to the Filiaşi labor camp. Of course the parishioners did not let me be taken to the construction site; I worked for 2 weeks until I received a telegram from the then President of the Community stating that the problems had been resolved, that I was exempted, that I could return home and fulfill my mission. It was a very difficult task, because we had to encourage the believers on whom the danger of deportation to the Auschwitz extermination camp was hovering. The mass deportation actually took place in 1944.

Here in Banat the danger of deportation was not deportation to the Auschwitz extermination camp, but deportation to Transnistria: some Jews (few) because they were involved in communist trials, others because they applied for a transit visa to the Soviet Union. - in order to reach America, all of them were nicely taken and brought to Transnistria and a group was exterminated. They - I think they reversed things - wanted to exterminate the group of those involved in communist trials and exterminated the other group. Their names appear on a commemorative plaque displayed on one of the walls of the ceremonial hall in our cemetery, here in Timișoara. (...)

About 30 co-religionists were deported from Timisoara for various reasons: some because they were part of the communist movement, others because they applied for a transit visa through the Soviet Union to reach the United States of America..., and they were deported. Some were exterminated. But, in fact, if we started here in 1941 with 12,000 Jews, in a city like Timisoara at that time, which had 80,000 citizens, when the war ended there were still 12,000 Jews, which is a rarity because we know very well that if there were 25,000 Jews in Oradea before the end of the Second World War, there were only 5,000 Jews on their return, because they perished in the extermination camps in Hitler's Germany.

When did you get married? In May 1948. The wife was from Timisoara? She was from Sighetu-Marmației. She was deported to Auschwitz. There are very few survivors. I don't know if there are 4 survivors in Timişoara - among those who were deported from Northern Transylvania to the Auschwitz camps. (...)

I wanted to ask you if before '89 there were conflicts in Timişoara between minorities and the majority, were they of an ethnic or religious nature? Locally, I can give a negative answer, because even during the communist dictatorship we were like brothers. Every holiday, Christmas, Easter, New Year or other occasions, the representatives of all religious denominations gather at the metropolitan residence. Since 1962, Metropolitan Nicolae Corneanu has been at the head of the Orthodox Church. He is an example, a model for all clergy, he is a great authority to whom we are bound by feelings of friendship, of appreciation, of love. Conflicts cannot be talked about. That the dictator Ceausescu was not a philosophit is without a doubt, because he encouraged anti-Semitic demonstrations, but locally we had no reason to complain. We lived a quasi-normal life, we had the opportunity to keep our faith.

You are one of the few who did not want to go to Erez Israel. Why? I'm not saying that my wife and I weren't tempted to leave at a time when there was still the first wave of emigrants. We thought that our place would be there, but at the same time we felt very connected to the community, to the city, to the country, and all these considerations made us stay put and to carry out the mission to which we have dedicated our whole lives.

A rabbi said that the Jewish life is based on three principles: teaching, divine service, and doing good. (...) We are a people full of life and desire for life, and in spite of all vicissitudes, we can say without boasting that, compared to all mankind, we have gained great merits in the evolution of this society, of human life, in all fields, not to mention the distant past, of the fact that we were the ones who, through the Sinai revelation, through Abraham, we rejected idolatry and became faithful to one spiritual God. By the laws of that morality, which have been revealed, the Decalogue is still and should be a guide for all people. It also includes the imperative "do not kill", because life is sacred and extinction is an injustice. If mankind would consider the principles set forth in the Book of Books, especially the visions of the prophets, then life would not have shown all the time, as it does today.

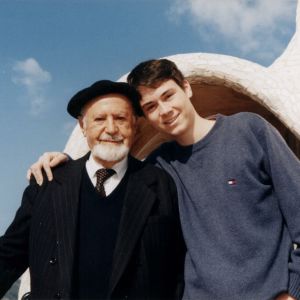

First Rabbi Dr. Ernest Neumann, born in 1917, Ceica, Bihor County - Excerpt from the interview resulting from the collation of two interviews, one conducted by Smaranda Vultur in November 1998 and another by Adriana Roșioru in March 2000, published in Memoria salvată, Evreii din Banat ieri și azi, coordinated by Smaranda Vultur, Polirom Publishing House, Iași, 2002.

In the Hebrew language, the Spanish Jews had the cult of the Sephardim, and the Orthodox and neologisms had the cult of the Ashkenazi, they were Jews from Germany, but also from Galicia, from Podolia. The Neologues were based in the Citadel, where the Community is still located today, but they had the great, famous synagogue. It was a house for the council, for general meetings, in Fabric, where it is now the house of prayer. In the fabric prayer house in Fabric, we managed to save the furniture of the Spanish synagogue in Fabric. The synagogue, built in 1889, in Fabric, following the model of the synagogue in Szeged (...) And then, in order to have a holy place, we took the great hall of counselors, where the council meetings were held and turned it into a house of prayer, and we took the furniture from the Spanish synagogue. Spanish Jews in Timisoara, I don't know if they are still there, they were: Schatteles, Bivas, families of Spanish Jews like Borgida, Aroesti; they spoke to each other in Ladino, a mixture of Hebrew and Spanish jargon, just as Yiddish is a jargon of German and Hebrew. (...)

Oscar Schwartz, born in 1910, Vienna - excerpt from the interview conducted by Adrian Onica in 2001 in Timişoara published in Memoria salvată, Evreii din Banat ieri și azi, coordinated by Smaranda Vultur, Polirom Publishing House, Iaşi, 2002.