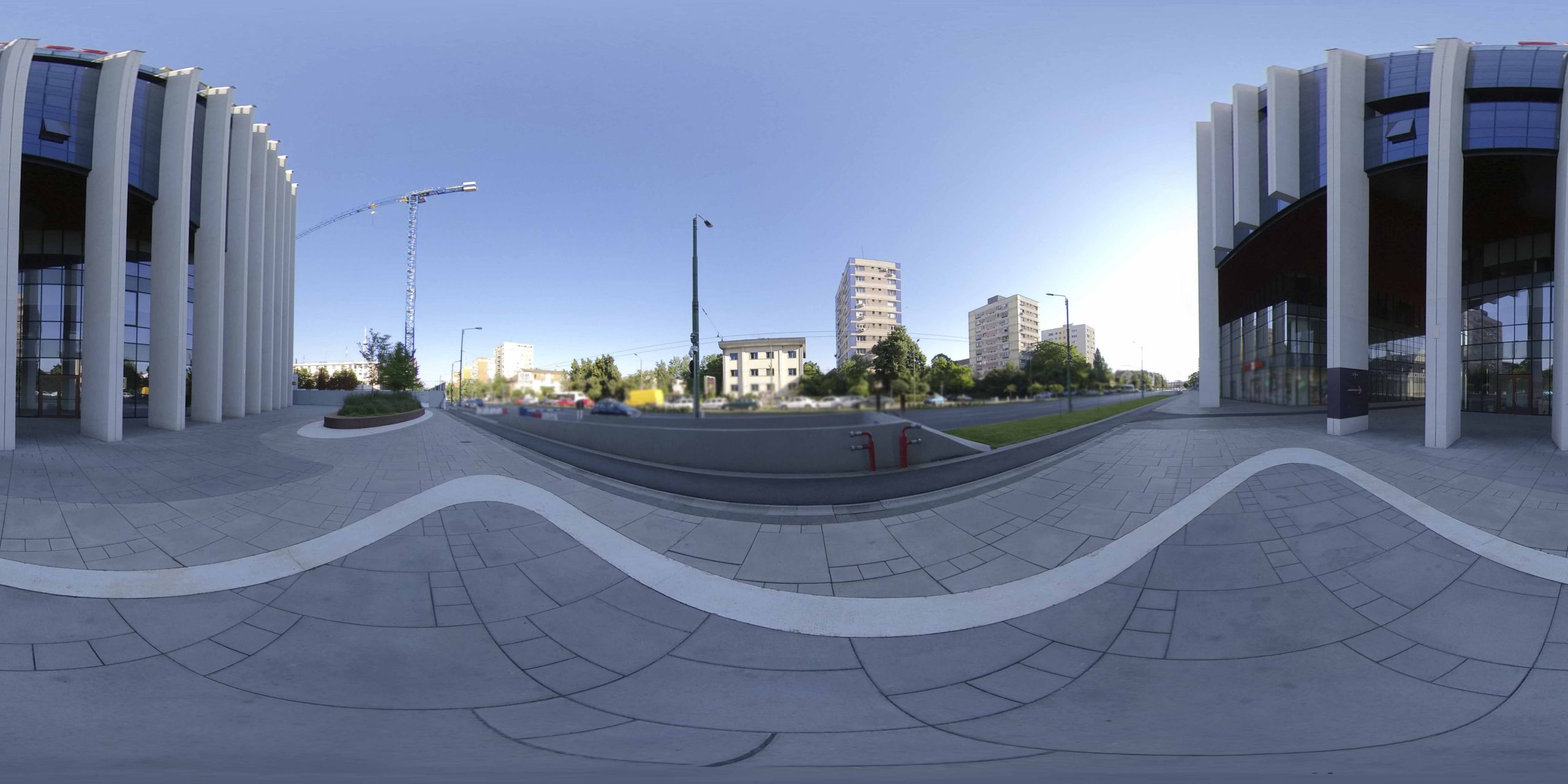

Fabrici-Faber, Peneș Turkey Square

After the economic crisis of the 1970s, the economy and especially the industry experienced an unprecedented development. The local or allogeneic investors founded during this period some of the representative factories of the city, many of them being built in the perimeter of the Fabric district.

Listen to the audio version.

After the economic crisis of the 1970s, the economy and especially the industry experienced an unprecedented development. The local or allogeneic investors founded during this period some of the representative factories of the city, many of them being built in the perimeter of the Fabric district.

Among the emblematic factories of the old Fabric neighborhood, we mention: Tedeschi & Comp. Foundry and Machine Building Factory, from Calea Buziașului street; Anton Novotny's Foundry; J. Anheuer safe-deposit box and car factory, opposite of the “Turul”; The brick factory on Calea Buziașului street, founded by Josef Kunz; Max Steiner Spodium Factory, which produced spodium, bone meal, bone fat, and animal coal; the Ladstätter brothers' straw hats factory; The soap factory in South Hungary, owned by Rudolf Hauser; The Kardos Gyula wagon factory, founded in 1905, which produced approx. 100-120 carts intended generally for the Balkan market; Wool Industry Joint Stock Company, which develops with the activity of director Rudolf Totis; “Turul” shoe factory, built in 1900 and put into use in 1901, which became in time one of the most important shoe factories of the monarchy, etc.

In addition, in Timișoara, there were numerous industrial units specialized in the field of agricultural products processing, wood processing, or in the field of construction materials and the chemical industry. This was a logical and organic continuation of the flourishing craft activity, which characterized the Timișoara economy in the previous period.

This development was favored by the measures taken by the local authorities to boost the industry in Timișoara. Thus, the enterprises established at that time in Timișoara received from the city authorities exemption from taxes for 15 years, free construction land, electricity at the manufacturer's price, as well as other subsidies.

In parallel with the industrial development of the city, there was a development of vocational education in the industrial and commercial fields, the two aspects being interdependent. The Timișoara industry, which had no less than 60 factories, surpassed the other cities of the province in the number of enterprises and could be compared with the most important economic centers of the dualist monarchy.

A faithful image of this upward evolution was provided by the industrial and agricultural exhibition in Banat in 1891, which enjoyed the presence of the sovereign Franz Josef I and was visited by a large audience.

The development continued in the interwar period when others were added to the existing industrial units, which contributed to the increase of the economic potential of the capital of Banat, under Romanian administration after the Great Union.

Bibliography:

Josef Geml, Vechea Timișoară în ultima jumătate de secol 1870-1920,Cosmopolitan Art Publishing House, Timisoara, 2016, pp. 88-96.

Factories – Faber

About Azur factory.I was born on April 8, 1930, to Manojlovic Milutin and Manojlovic Zagorca, who had met at my aunt’s wedding in Novi Sad, where my father was - in English, there’s “the best man” - the best friend of the groom. He was a bachelor and he was the big boss of the factory and a shareholder in “Azur”, which was then named “Excelsior”. He was very well off, he traveled the world. He was very handsome... He was very handsome, indeed - this picture is not relevant, but I do have others. What about your mother? Mom was very pretty, she had blonde hair and blue eyes. Dad had brown hair, he was a bit dark-skinned, and tall. Mom was also quite tall. He was very good-looking... He looked very well indeed - this picture is not relevant, but I have other pictures. And your mother? My mother was very pretty, she was blonde with blue eyes. My father was brown, a little creole in the face, he was tall. And my mother was quite tall.

And my mother had left college for a week to attend her older sister's wedding. Your mother was a student in... in Vienna, at medicine. And she came to her aunt's wedding and fell out with my father, who was eager to marry her. And my mother wouldn't give up medicine, she was very serious and very studious. She was a Yugoslav state scholar in Vienna, so not anyway. And in those days girls didn't go to high school. My aunt, who married a very rich merchant, Nenadovic, had her own staff: cook, maid, two nannies for the children, etc., she was pestering my mother to marry this Mr. Manojlovic, who is a great catch, and a good guy. What does she need medicine for?! Look, he's the director and shareholder of the Excelsior Paint and Lacquer Factory. My father went to Vienna as often as he could and took my poor mother to the opera and persuaded her to marry him. My mother had no idea how old my father was, and the day she signed the marriage papers she saw that my father was thirteen years older than her, and she almost fainted. (Laughs.) How old was your mother? When she got married, twenty-three. And my father was thirty-six.

Xenia Manojlovic, born in 1930 in Timișoara – excerpt from an interview by Simona Adam, in Timișoara, 2002, The oral history and anthropology group archive, coordinated by Smaranda Vultur.

About Banatul factory. Here was the first nursery and the first kindergarten in the city, at Dermata, you may ask around. It the beginning, Banatul factory was called Dermatitis from Timişoara, just like the factory in Cluj. When Dad was the manager here, he set up the first nursery and a kindergarten. Dr. Muţiu, who in the '80s was still a manager at the Children’s Polyclinic here, worked as a doctor at the kindergarten in his youth. For the employees’ children? For the employees’ children. I told my father: “Dad, why won’t you buy us a quartz? You only buy them for the clinic and we don’t have a quartz lamp.” Ultraviolet lamps used to be called quartz lamps. And he told me: “no, because when you need one, I’ll send you to Dr. Corcan - a famous pediatrician in Timişoara – and he’ll give you as many UV sessions as you need. These children can’t afford it and that’s why I buy the lamps for them.” He would also often pay for the meat and for other stuff, so that they’d have everything they needed. And let me tell you, as a sidenote, now at the centenary anniversary, where I was invited and I received a diploma for my father, in the presiding committee there was prefect Ciocârlie, the mayor, someone from Bucharest from the Ministry for Industry, and when they projected my father’s picture on the screen I started to cry. And manager Cazan, who is the general manager here now, also said: “he was a remarkably good man, you know.” When I stepped inside the factory, my heart sank. I was called twice to say what was where and I said here was the sewing floor, here was this, here was that and she says, “but you remember it well.” How can I not remember, I was 7-8 years old, but such memories won’t just go away! There was no exception, for Christmas and for Easter, the children of the workers always got some gift.

Marieta Anhauch, born in 1937, in Chernivtsi – excerpt from an interview by Antonia Komlosi, in Timișoara, 2005, Bessarabians and Bukovinians in Banat (Basarabeni şi bucovineni în Banat. Povestiri de viaţă). Life stories, 2nd ed. Brumar Publishing House, Timișoara 2011.

Despite the poverty, as we were all workers and lived on small wages... the factories were whistling and ... There were many factories around here, in Fabric. First of all, there was the Leather and Glove Factory, then Teba, 1 Iunie, the Sock Factory in Badea Cârţan. Also at the market, near the bridge, there was Ilsa, where they produced fabrics. There were workers everywhere. There was the Railway Coach Factory, Guban and many more ... There were also smaller ones: the Rubber Factory, footwear workshops, Texta, Filt. Everyone worked in factories, women, men, young people, everyone. Once you’d finished 7 grades, at the age of 14 you became an apprentice and started work… So everyone had a job and that’s what they lived on. There were no unemployment benefits or... there wasn’t such a thing. There were some layabouts at the market, who would help the ladies with their shopping baskets, who helped around with this and that... and got some money in return.

Sipos Péter, born in 1925 – excerpt from an interview by Antonia Komlosi, Timișoara 2003, The oral history and anthropology group archive, coordinated by Smaranda Vultur.

About the glove factory

No Jewish friends? Industrialists? Industrialists, no, but there were some who worked in the factory - there was a Ritter, there was a Berger... But most of them went to Israel afterwards. So where was the factory? It was in Fabric, also on the bank of the Bega river, and it was called "Splaiul Morarilor". After the Turkish Prince? I don't know exactly. Straight ahead, after Traian Square. There was IRP (Romanian Leather Industry), there was Westendt (?), for gloves and there was "Ideal" - for shoes. So he bought twelve houses that were around. When he moved out of Oravita, he wanted workers to come, that he brought from the West, from Switzerland, France and even Italy, some people who taught him how to make patterns, which is a trade, not just machine work. And they were very skilled. In Timisoara he couldn't find any of these workers, and to bring them to the factory he bought 12 houses around the factory to house them. And they all came, with their families. Where in Oravita were these...? You know, in Oravita there's a street, the main street, and they were in Romanian Oravita, at the bottom. Towards the Greek Catholic church? That's right. Are there still buildings from that era? There are, there are. What's there now? They're private. About how many workers were there in Oravita? Two hundred - two hundred and fifty. And he brought all 200 with him? He brought them, yes, because they wanted him to. There was no work in Oravita. I would like to draw your attention to the fact that there was a Prefecture in Oravita when I was born, and after the factory was closed, this town was no longer of any interest, and it (the Prefecture) moved to Reșița, where there was industry. When I was born, the current Town Hall was the Prefecture. So that's where the glove factory and the shoe factory were? No, the shoe factory was created in Timisoara. It was the glove factory and it was leather. And Timisoara also made this shoe factory - "Ideal". Yes, yes. The gentleman I was just talking about, from the French Centre, was a very nice guy, and he showed me the house... And he said: "I was told here in town that your father had some factories." "Yes. Why?", I say. "I might have some customers." "Well, that's what interests me!" I gave him my phone number, never heard from him again, and one day I open the newspaper „Le Figaro” and see on two pages that the French are investing in Timisoara because there are much more serious people there than in France. I thought that was really true, and that they wanted to start a business and I don't know what... So, I rush to the phone, call that one. He says, "Yes, I just have a gentleman here looking, and I'd really like to be the go-between." And I have a friend there in Timisoara whose father lived two steps away from the factory, so he had located it. I say, "Listen, would you go with these French people and show them?" "Yeah, sure." He goes to the French Cultural Centre, I of course called that gentleman we know, and he went with the French client... Yes. And they went with the French industrialist who wanted to buy a factory. And the doorman comes out and says, "It's sold." I was never notified. (And who did this?) As far as I know, some Pakistanis were five people, they made fur.. The factory is empty, it's totally deteriorating, I went with the one who knew where it came from... Who could have sold it? The Romanian state? The Romanian state, yes. And what hurts me is that the factory doesn't work, because if it worked it would bring in money and I'd be happy with that. The roof is totally broken, and where no one stands, it always gets damaged, everywhere is like that. That's it! Did the factory work until you left?And after that. It was confiscated in '48...

Through the N.T.O. we came to Timisoara. I wasn't allowed to stay with them, with my grandparents, I had to stay at the Hotel "Banat". And a lady came and told me she would show me Timișoara. I told her: "You know, I'm not really rich, I paid a lot for this hotel and I want to stay with my grandparents, I know Timișoara." "Yes, but that's the program. I'm sorry, ma'am, but you have to!" And then she came with a car, with a taxi, and first she took me to the Cathedral, as if I didn't know where it was. I liked the Cathedral very much, especially since King Michael came to inaugurate it. They inaugurated it in '46. And, anyway, before I went there I went to see it again, so I didn't need to... Especially since it wasn't far from the hotel.

And two days later,s he calls me again at the hotel: "I've come for you, I'll show you the city again". And I wasn't happy, I didn't need it. I only stayed eight days and it was the grandparents' class. But she took me to the factory, and I went in. And what factory was there? There were fur. In our time there was leather, and leather that was exported, it was very beautiful leather. Now it was fur, whatever. Did she take you by chance, or did she know? No, she knew, yes, yes. But she told me that was part of the program, that she was taking other foreigners. Anyway... What year was this? That was in the '60s.

Where did he do his studies, your father? He studied partly in Budapest, there was a Commercial Academy, then he came to Paris for law and finished in Cluj. He did a doctorate in law in Cluj. And how did he come to have connections with the French, in what context? The French came to Timisoara quite often, they visited the factory. He had friends. So through industrial relations. Did they import products from the factory? Yes. The Westend(?), which was the glove factory, had the first prize at the '37 exhibition in Paris. The gloves were very elegant. And why he came to Paris: the great-grandfather I told you about, the Austrian, had an apprentice. The house in the back had apprentices. And he was the son of an illiterate forester. And one day he said to my great-grandfather: "You only have one daughter, she got engaged. Moldovan won't take the bakery and confectionery. If I get the money later, will you sell me the shop?" And his great-grandfather said, "Listen, Eftimie, you know you're worth more. You can do more than just be a baker. Go out into the world, cultivate yourself!" And when he found he couldn't write well, he made him learn. And at some point he went to Constanta, got on a ship and came to the West. He lived I don't know how many years in Germany and ran into Hitler. He went to see Wagner's operas, because that was Hitler's passion. And Hitler wanted to persuade him to become a Nazi, to adopt his ideas. But Gherman, who was a good man, thought that this was not something he liked and returned to Romania. What was he? Romanian. Eftimie Gherman is well known in the Caras. In the meantime the whole family grew and my father joined the family. Gherman went to see my grandfather Moldovan, whom he knew very well, and told him: "I would like to become a politician." And in the meantime he became a socialist. But my grandfather was still a social democrat. And they supported him, financed him and he became an MP. But at some point the communists and socialists disagreed and he left Romania and ended up in Paris. So he arranged it here, so we could get in, together with my father's French friends. It was very difficult, because all Romanians were considered spies. So they didn't let us in so easily. After that, I frequented him a lot in Paris.

Mariana Duval, born Langer in 1935 in Oravița - excerpt from the interview conducted by Smaranda Vultur in 2005 in Paris, published in part in Memorie și diversitate culturală la Timișoara - Meserii și meseriași, authors: Smaranda Vultur, Vlad Colar, Thomas Remus Mochnacs, Gabriela Panu, Brumar Publishing House, Timișoara, 2014.

Foreigners bought goods from us... I can tell you about the Glove Factory, which was small at the beginning, with 100 workers, and then it expanded, it had 4000 people, exporting to Germany, America, Russia. And they went to India and China for skin and fur. In order to have the quality demanded, it bought machines from abroad. But they got machines that were already old there.

That's the way our trams are... And in the end the competition drove us out of the market because of our low quality. And in the end no one bought from us anymore. And development has a condition: if you don't produce, you can't live. Many are unemployed. At the Glove Factory, out of 4,000, 100 people still work. At Ilsa the same, because there's no more fabric. They bring cheap, bad clothes from abroad and people buy them because they can't afford other clothes. Nowadays there is no longer any suszter - shoemaker, to put a sole or a heel on your shoes. This is a profession that has almost disappeared. Tailors are no longer in demand. Nobody makes their own suits anymore, they buy them ready-made.

There is no more kádár - those made barrels. Now it's plastic barrels, right? Can you imagine what a job it was to be a kádár when so much wine and brandy was made in the villages that they needed barrels? There were also 1000-litre barrels and smaller. It was a job that is no longer necessary today.

"What were the best jobs in Timișoara? And who did what? You said, for example, that the Jews had the most shops."

Each trade had a Craftsmen's Association, where craftsmen met and discussed prices and all sorts of other issues. With carpenters, there were those who made lacquered and painted bedroom furniture, there were those who only made kitchen furniture and so on, by specialisation. In order for someone to open a craft workshop, they had to go to the School of Craftsmen first. After graduating from the school, they had to work for at least three years as an apprentice. Then they had to register for a master's exam... every town had such workshops. There, for a week, he had to do his trade and, in addition, he had to take a theory exam. And only after all that could he open a company, to make furniture.

There was a lot of competition! The shoemaker would put out three or four pairs of shoes and if they were nice, people would come in to see and buy. There was competition, whoever didn't know how to make something of quality went bankrupt, couldn't exist. They went to work for other people as shoe-makers or did something else.

There were Dermata Factory Stores, Tour... that made beautiful ladies' shoes. It was hat fashion: women and men wore hats all day long. Children and schoolchildren wore hats and adults wore hats. They weren't with headscarves or bare heads - no! It was elegance. They weren't overpriced, but they were quality. My brother-in-law for example, when he got married 25-30 years ago, got a pair of lacquer shoes combined with suede... beautiful, thin-soled, and they still fit him. Second-rate stuff couldn't sell because there was competition and demand. Companies that cared about quality stayed in business, and the rest closed.

And now if I walk down the street I can count how many LLCs are left and how many have closed. They all wanted to trade... but you have to know.

A lot of times I'm looking for something and I can't buy it, I can't find it. I can't find shoe laces, a sole, a place to fix a pair of scissors... gone. You can't find a quilt to fix an armchair, a lounger, something! There are no more shops where you can go to find certain little things. There used to be shops where you could buy everything from kerosene for the kerosene lamp to salt, sweets, everything. You'd walk into the store and you could shop all week. And they'd bring it home. My handyman's mother had a spice shop and every day she would get 1,000 kg of wood. We, the apprentices, carried it in. They were chopped and sold by the kilo. A man could only buy 50 kg of wood if he wanted.

Everyone had work to do. It was a balanced, harmonious life. People weren't, I stress, they weren't so pretentious. Today people are pretentious and would like to live well without work. Back then people were not hungry for wealth, like today. Fabricul, EntreVii - these neighbourhoods - were formed around the city. Two husbands, like my sister and her husband, worked as pantographs in a factory and bought land in instalments (from a landowner who sold land in plots). They paid one salary in instalments and lived on the other. After they paid for the land, they also built a fence on debt. Then they made a well and if they didn't have money, they made a well out of mud with clods and from that they built the house. Slowly, slowly, the houses were built, but not with great effort. You had to work very hard... and everybody worked... but it was done.

There were also those who sold different things. An egg was 90 cents. If a peasant woman came with 500 or 1000 eggs and didn't have time to sell them because she had to go back to the country, she would give them away for 70 cents and the seller who took them would sell them for 90 cents. That was also a way to make money, to make a living. Chickens were cheap. The peasants kept pigs, about five or six, two of which they cut and the rest they sold.

Let's do the math. I earn 10 lei in an hour, which is 10 eggs in an hour. A bigger watermelon cost 3 lei, but you wouldn't pay more than 5 lei for any watermelon. My father and I used to go to the hay market (Badea Cârțan Market today) with the wheelbarrow and we would get melons, because my father was good with melons, and we would eat our fill. We ate so much that we were swimming in watermelon. You could afford it, not like now. There was a story in the newspaper recently about a woman who went to the market and got a big, expensive watermelon. She took it home and when they cut it up it was pumpkin. The husband was upset that she had paid so much money and didn't know anything about watermelon, so he went to buy it. He picked it out, felt it and when he took it home it was still pumpkin. In the end, the journalist wrote, they gave so much money and still didn't eat a watermelon. Hand in the bag. The people who bring the watermelon don't care what they sell. They pick it early and don't let it ripen. Besides, watermelon farming is a job. You have to be good at it, so not everybody can do it.

Horwáth Lajos, (Lali) born in 1921, in Becicherecu Mic - extract from the interview conducted by Antonia Komlosi in Timișoara in 2001, The oral history and anthropology group archive, coordinated by Smaranda Vultur.

About Azur factory.I was born on April 8, 1930, to Manojlovic Milutin and Manojlovic Zagorca, who had met at my aunt’s wedding in Novi Sad, where my father was - in English, there’s “the best man” - the best friend of the groom. He was a bachelor and he was the big boss of the factory and a shareholder in “Azur”, which was then named “Excelsior”. He was very well off, he traveled the world. He was very handsome... He was very handsome, indeed - this picture is not relevant, but I do have others. What about your mother? Mom was very pretty, she had blonde hair and blue eyes. Dad had brown hair, he was a bit dark-skinned, and tall. Mom was also quite tall. He was very good-looking... He looked very well indeed - this picture is not relevant, but I have other pictures. And your mother? My mother was very pretty, she was blonde with blue eyes. My father was brown, a little creole in the face, he was tall. And my mother was quite tall.

And my mother had left college for a week to attend her older sister's wedding. Your mother was a student in... in Vienna, at medicine. And she came to her aunt's wedding and fell out with my father, who was eager to marry her. And my mother wouldn't give up medicine, she was very serious and very studious. She was a Yugoslav state scholar in Vienna, so not anyway. And in those days girls didn't go to high school. My aunt, who married a very rich merchant, Nenadovic, had her own staff: cook, maid, two nannies for the children, etc., she was pestering my mother to marry this Mr. Manojlovic, who is a great catch, and a good guy. What does she need medicine for?! Look, he's the director and shareholder of the Excelsior Paint and Lacquer Factory. My father went to Vienna as often as he could and took my poor mother to the opera and persuaded her to marry him. My mother had no idea how old my father was, and the day she signed the marriage papers she saw that my father was thirteen years older than her, and she almost fainted. (Laughs.) How old was your mother? When she got married, twenty-three. And my father was thirty-six.

Xenia Manojlovic, born in 1930 in Timișoara – excerpt from an interview by Simona Adam, in Timișoara, 2002, The oral history and anthropology group archive, coordinated by Smaranda Vultur.

About Banatul factory. Here was the first nursery and the first kindergarten in the city, at Dermata, you may ask around. It the beginning, Banatul factory was called Dermatitis from Timişoara, just like the factory in Cluj. When Dad was the manager here, he set up the first nursery and a kindergarten. Dr. Muţiu, who in the '80s was still a manager at the Children’s Polyclinic here, worked as a doctor at the kindergarten in his youth. For the employees’ children? For the employees’ children. I told my father: “Dad, why won’t you buy us a quartz? You only buy them for the clinic and we don’t have a quartz lamp.” Ultraviolet lamps used to be called quartz lamps. And he told me: “no, because when you need one, I’ll send you to Dr. Corcan - a famous pediatrician in Timişoara – and he’ll give you as many UV sessions as you need. These children can’t afford it and that’s why I buy the lamps for them.” He would also often pay for the meat and for other stuff, so that they’d have everything they needed. And let me tell you, as a sidenote, now at the centenary anniversary, where I was invited and I received a diploma for my father, in the presiding committee there was prefect Ciocârlie, the mayor, someone from Bucharest from the Ministry for Industry, and when they projected my father’s picture on the screen I started to cry. And manager Cazan, who is the general manager here now, also said: “he was a remarkably good man, you know.” When I stepped inside the factory, my heart sank. I was called twice to say what was where and I said here was the sewing floor, here was this, here was that and she says, “but you remember it well.” How can I not remember, I was 7-8 years old, but such memories won’t just go away! There was no exception, for Christmas and for Easter, the children of the workers always got some gift.

Marieta Anhauch, born in 1937, in Chernivtsi – excerpt from an interview by Antonia Komlosi, in Timișoara, 2005, Bessarabians and Bukovinians in Banat (Basarabeni şi bucovineni în Banat. Povestiri de viaţă). Life stories, 2nd ed. Brumar Publishing House, Timișoara 2011.

Despite the poverty, as we were all workers and lived on small wages... the factories were whistling and ... There were many factories around here, in Fabric. First of all, there was the Leather and Glove Factory, then Teba, 1 Iunie, the Sock Factory in Badea Cârţan. Also at the market, near the bridge, there was Ilsa, where they produced fabrics. There were workers everywhere. There was the Railway Coach Factory, Guban and many more ... There were also smaller ones: the Rubber Factory, footwear workshops, Texta, Filt. Everyone worked in factories, women, men, young people, everyone. Once you’d finished 7 grades, at the age of 14 you became an apprentice and started work… So everyone had a job and that’s what they lived on. There were no unemployment benefits or... there wasn’t such a thing. There were some layabouts at the market, who would help the ladies with their shopping baskets, who helped around with this and that... and got some money in return.

Sipos Péter, born in 1925 – excerpt from an interview by Antonia Komlosi, Timișoara 2003, The oral history and anthropology group archive, coordinated by Smaranda Vultur.

Listen to the audio version.

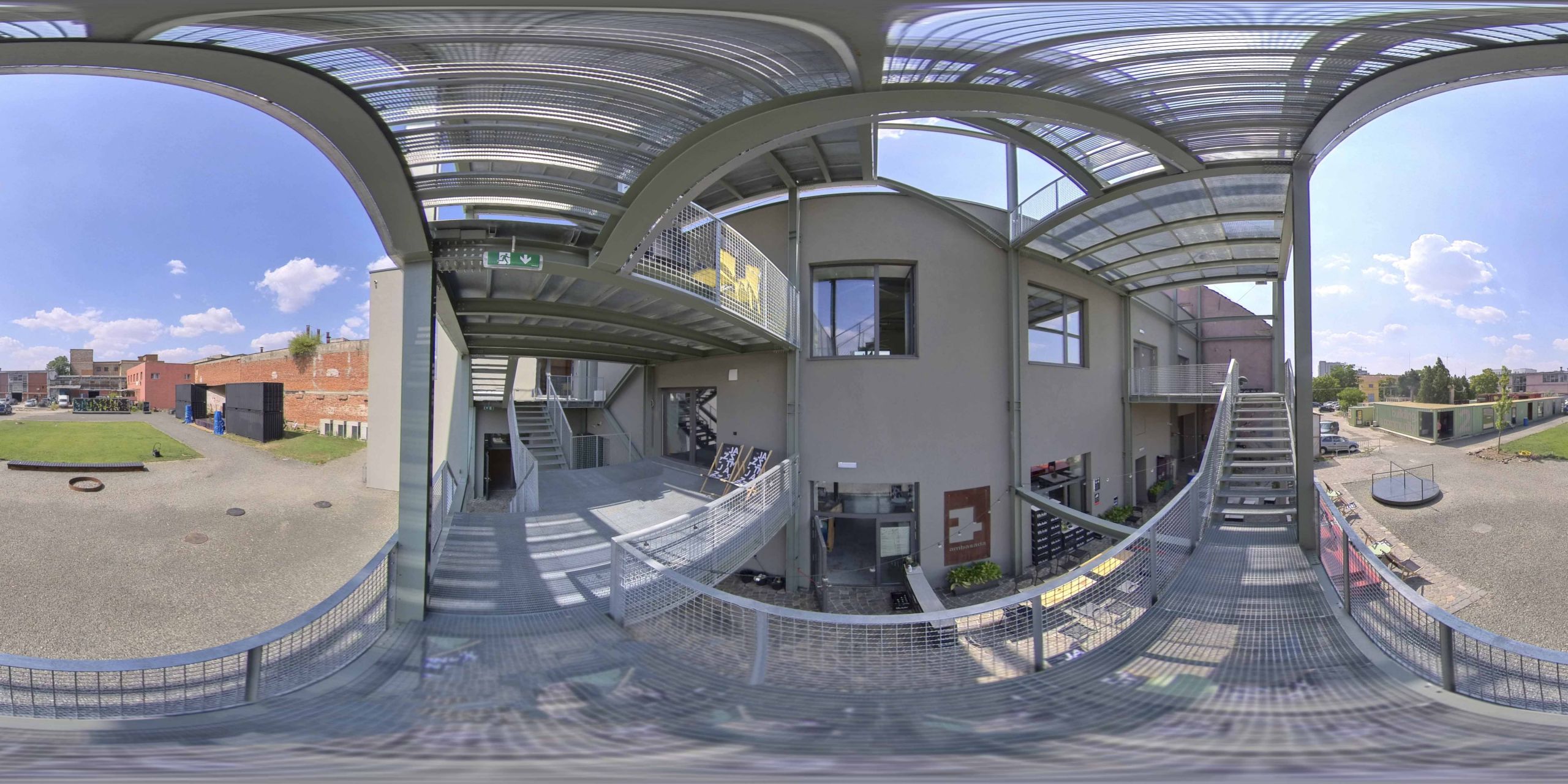

Free rein to Faber Factory

Faber Factorywhat it was and where it ended up. We can say that the modernisation process that has taken place over the years is perfectly represented by the transformation it has undergone Faber factory. From what was considered a ruin, with a story behind it, new future stories were started, including my story. Now Faber Factory (station 14) is more than just a refurbished and redeveloped ruin, it is a place where a whole community has formed and I can say that I too consider myself part of this small gathering of beautiful people. The place has really flourished. A green space, full of art, creative spaces, places to relax and let's not forget the coffee shop that intertwines everyone's desires, the Embassy, nothing is more pleasant than having a good drink, a coffee full of flavours, while feeling free and peaceful. For me personally it's a whole experience to go and drink a coffee, made from coffee beans roasted right in their courtyard, lying in the sun, watching the kids running free through the grass and the relaxation on the faces of the people around. I remember with pleasure every coffee I drank with my friends in this special place in Timisoara. As a tradition, I can already say, we get to meet there as often as we can and talk every time, but every time I tell you, about the same subjects, their pets, more precisely a friend with three dogs, and another friend with five cats, a madness. Then follow the ever-present stories of love and craziness experienced at all sorts of parties, which I can't divulge here but you can imagine, it's not for nothing that we're in our twenties, we have to experience freedom while we can (as they say). And to end the whole discussion on a not necessarily good note, but you know how man is, he has to complain about something, we sadly remind ourselves that there is still a little, even a little bit, to go before "life hits us", as we say. But you realise that we are kidding ourselves, we just know that life always has something good in store for us no matter what age we are.

This is how I remember this place every time, with good and bad, but most importantly with many memories with my girls. And who knows, maybe in the future, after more meetings in this place I will tell another story about how I remember the Faber Factory and the Embassy.

The Faber Factory is now a place that brings the community together and brings people together in a non-conformist space where you can let your imagination run wild, as I do with my girls every time I come there!

Elena Nichitean, UPT Student, 2023

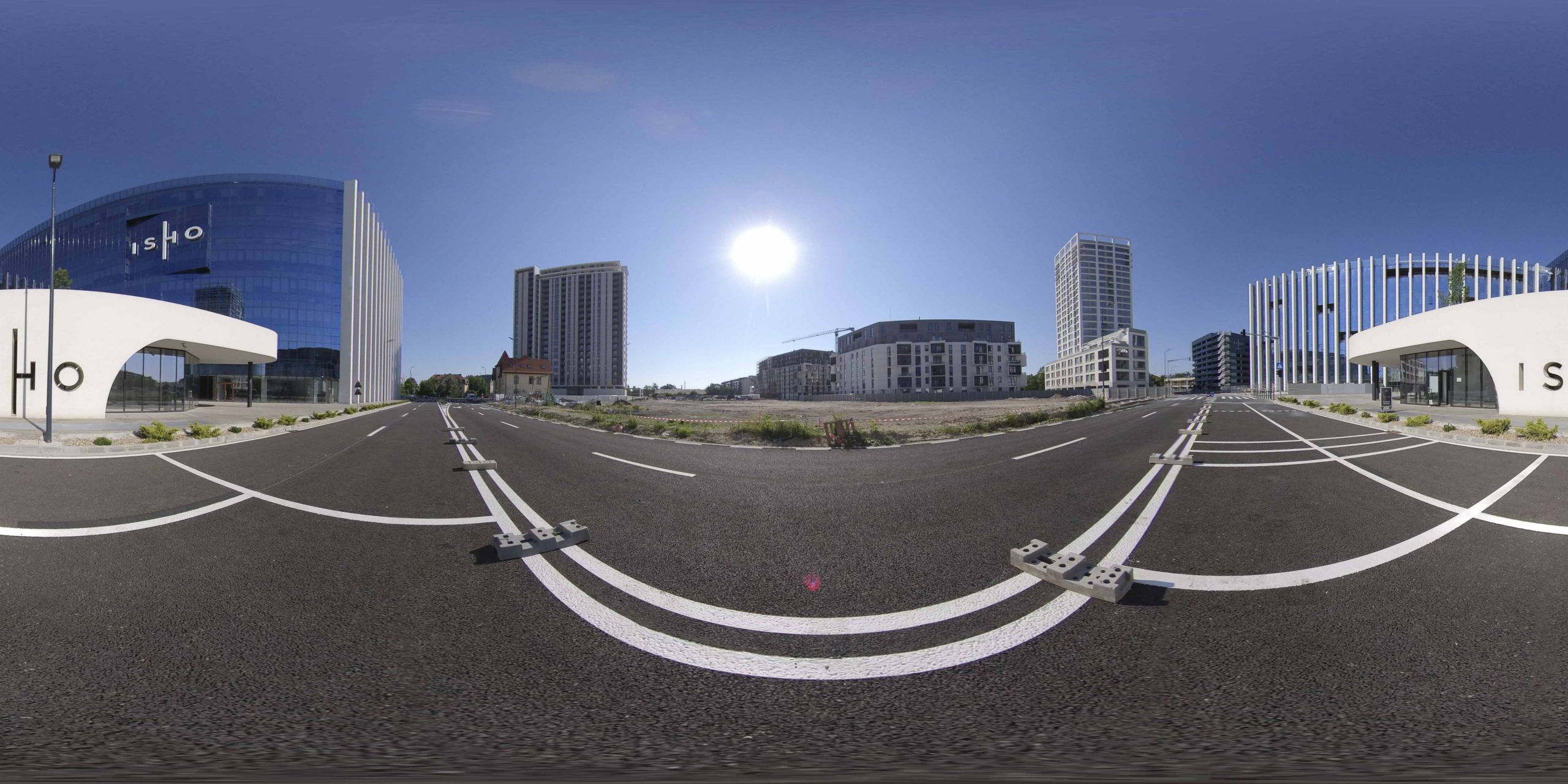

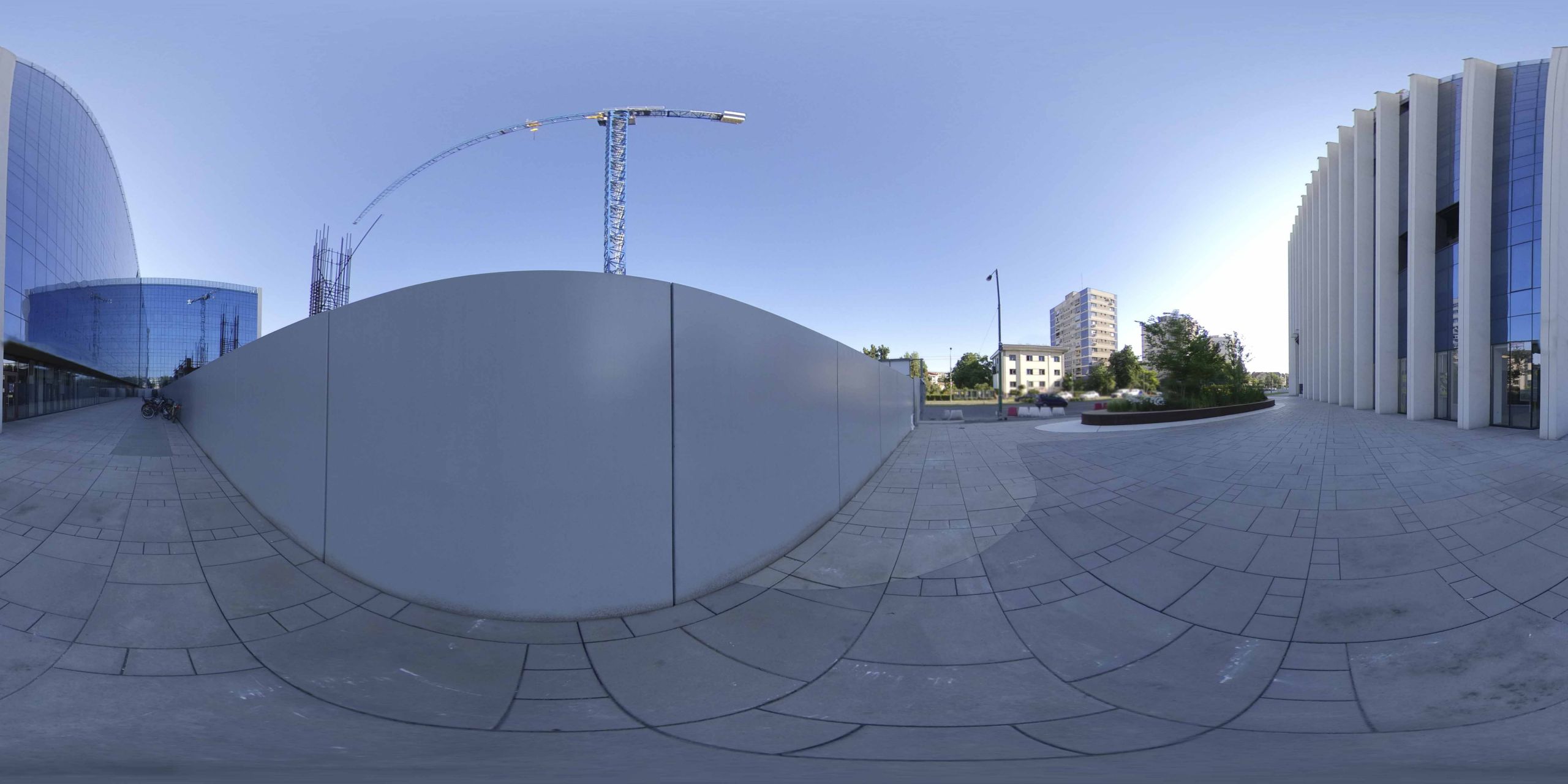

FABER building is part of a former industrial site important to the city in the Fabric neighbourhood of Timișoara, on the bank of the Begă: the former United Oil and Soap Factoriesnow known as AZUR. The site is important because it represents the original location of a business that after the communist period returned to the family that started it, the Farber family. Today, the former industrial site is home to a long list of small entrepreneurs and artists, while the owners have not yet thrown themselves into brutally reformulating the contents of the plot, even though they have not had any industrial activity here for more than half a century.

From an urban planning point of view, the site is in the middle of an area in transition, which according to the future city's PUG must be transformed into a mixed-function area. Although there are various discussions about how this development could be developed, the building FABER is the first to be rehabilitated.

The building has a built-up area of approximately 840 sqm, structured and distributed almost equally on two levels - ground and first floor. In terms of functions, the ground floor accommodates a large event room, an access foyer, toilets, a bistro area with the associated kitchen as well as a gangway that provides car access to the plot. The first floor consists of the coworking area and makerspace, along with 2 medium-sized meeting rooms and 2 small, overlapping meeting rooms. The vertical circulation is speculated in the form of a complex apparatus, composed of stair ramps and bridges/platforms that provide both access to the floor spaces and the possibility for various outdoor activities, culminating in a belvedere overlooking Bega and the city.

The organisational structuring reflects the spatial needs of each, so AMBASADA operates part of the ground floor, the coworking operator, FOR operates upstairs, and FABER manages the large event room and one of the medium-sized meeting rooms upstairs.

AUTHORS: F O R - Simina Cuc, Alexandra Maier, Pepe Peralta Guerrero, Alexandra Rigler, Sergiu Sabău, Oana Simionescu, Maria Sgîrcea, Alexandra Spiridon

FABER PARTNERS: Cristina Potra Muresan and Valentin Muresan, F O R, AMBASADA, Adrian Erimescu.

Address: Peneș Curcanul 4-5, Timișoara