East Railway Station, Avram Imbroane Street no. 1

Opened in 1886 on the Timișoara - Caransebeș railway, Timișoara Est Railway Station, former Fabric Station, is one of the five railway stations in Timișoara.

Listen to the audio version.

Opened in 1886 on the Timișoara - Caransebeș Railway, Timișoara Est Railway Station, former Fabric Railway Station, is one of the five railway stations of Timișoara, being considered the second most important railway station after the North Railway Station, being an important railway junction freight.

In 1886, the Timișoara - Orșova line was built, which connected Bucharest, Istanbul, and Sofia, the Eastern Railway Station reaching the situation of taking over a large part of the traffic from Iosefin station (North Railway Station Timisoara), particularly the freight one.

Due to the presence of a significant number of factories and enterprises in this area, Gara de Est provided the materials and took over the goods from these economic units, there was also a line that connected to the network of tram lines, with the same gauge. The operation of low-power electric locomotives was important, being able to operate up to four wagons of 10-15 tons each, on two axles, the locomotives being provided with buffers and couplings. The wagons were taken from the connection line to the tram network, which crossed The Traian Square. All these lines have now been taken out of use. Thanks to the movement of goods and passengers, the station building was expanded after 1899, comprising a central body and two secondary wings, while increasing the number of lines. In 1970, the building was modified by arranging a floor.

Bibliography:

Valentin Ivănescu, Illustrated chronicle of the Timișoara Railway Regional, 2009, in pdf format on the Banaterra website, Timisoara

East Railway Station

Imbroane Villa - about the Avram family and Sofia Imbroane

So you met Avram Imbroane. Certainly. He was a smart man. He was part of the Banat elite. They were all part of the Banat elite: Cosma, my father, Cornel Corneanu, Imbroane, they made the best government, and the Romanian country prospered. The government of 1933 -1937, when my father was a vice-president of the senate. Imbroane was also there, with my father in Alba-Iulia. Cornel Corneanu spoke very nicely. We had a train available to go to Lepădat's celebrations in Cluj, because he turned 60 years old. We used to say he was old. But look, now at 88 I'm still young. Cornel Corneanu spoke on behalf of the National Liberal Party. They put a Banat resident to talk. Tătărescu was then and he put Corneanu. I have known Bishop Nicolae Corneanu since he was a child. I've been a church counselor all along.

I consider that between the two world wars, the outstanding personalities from Banat, apart from these professors who were in Timişoara, at the Polytechnic, were Băran la Vaidiş, who struggled, but who had an extraordinary role in the construction of the Cathedral. My father also played an important role in the construction of the Cathedral. My father went to Duca and said: "Mr. President, now Caraşu is new, it is done by you, and we must give him prosperity." And Duca agreed. We had the U.D.R. here in Resita, and it took over the Orthodox church fortunes. The U.D.R. were the Resita Domain Plants (Uzinele Domeniilor Reşiţa) and the general manager was the Jew Auschnitt. So my father said to Duca: "Please, Mr. President, talk to Auschnitt." Auschnitt was a liberal, and among the banks was Marmorosch Blank, also a liberal Jew. There was also the Romanian Bank, also made by the Liberals. Duca told my father: "Alright, come to me tomorrow at this time." That was before the 1930s. He also invited Auschnitt and told him: "Mr. General Director, this is Father Archbishop Musta of Oraviţa. He is both a political and a church figure. What he asks of you, give him.'' Auschnitt, of course, listened to him. My father went and did all the churches. Oraviţa Cathedral is very beautiful. The iconostasis is in gold. The reconstruction of the church officially cost 300 thousand. My father went to Auschnitt and told him that there wasn't enough money. He gave my father another 300,000 from protocol, but that wasn't settled. So officially it cost him 300,000, but it was 800,000, because he asked for another 200,000 and he got them. He built the church in Anina. He made a cultural Center in Sasca. My father went to him and said: "Look, this is what we need here" and he gave the money right away. In all the mountain villages: in Sasca, in Ciclova, Oraviţa. My father exploited and gave it to the villages that were not mountain villages, also from that money. He enriched it beautifully. All the churches were repaired during his time. He was a famous archpriest. Until 1931, his uncle lived there also and died at the age of 91. That's life. My father was, I think, a bigger personality than Băran, who was also a minister in Vaida, but later. Lugoj had personalities, Timişoara had personalities, and among them was my father. Was Lugoj stronger than Timișoara? o, no, but it was more Romanian in strength. Timisoara was a Hungarianized and Jewish city and had many Germans. But in Lugoj there were only Romanians.

What role did Imbroane play? He had the role of former secretary general of the Cults. But until then? Until then, he had been in the National Party, and after that he went to the front and became a prisoner of the Russians for a year. After being taken prisoner by the Russians, he became a publicist in Bucharest and Timişoara, and after that he moved to Timişoara. He was a publicist, a journalist in Timișoara. He lived well, because he was a gifted man. Vasile Loichiţă was a former rector of Cernăuţi, a great Banat personality. These were the people of Banat who led during that period, including my father.

Did Imbroane play a role in the Union? Well, he went to the Union with my father. Bishop Miron, the representative of the two churches, was not present at the Union because he went to teach Transylvania to Brătianu, in Bucharest. Neither Hosu nor Miron were at the Union. Miron was the bishop of Caransebeş and he was the godfather of my father, because the meeting was presided over by my father's uncle, Filaret, the vicar, and the bishop Musta. For Filaret, everyone had an extraordinary esteem, because he was an extraordinary Banat personality before this century and after that my father came, who I can say was the second Banat personality, it is not a small thing to be vice-president of the Senate. It was Titus Popovici, the minister, who was from Lugoj and was a liberal from a young age.

In 1926 Avram Imbroane became party president with Nistor, who later became prefect. Aurel Cosma died in 1931. But Imbroane took his place in 1926. Imbroane led from 1926 to 1936, helped by Nistor, who was mostly in Bucharest. Timisoara did not have such an organization. The first on the Liberal list was Richard Franasovici, who was from Turnu Severin and was the Liberal Minister of Communications from 1933 to 1937. Until 1933 he was a permanent deputy in the Romanian parliament. He was a great man, so to speak. Also on the list was Brânzei, a French teacher.

And in what period was Imbroane a deputy? Imbroane was a deputy once, in the 1920s, and I think in the ’23, with the Liberals, and after that he was the general secretary of the party. Cornel Corneanu was also the vice-president of the Chamber of Deputies, and my father was the vice-president of the Senate.

Did you meet Sofia Imbroane? Certainly. She was the president of the Housewives Circle. So did my mother, the president of the Orthodox Women's Circle, because my father was an archpriest and therefore to gather more people to talk to them. Then there were more circles than societies. There were church and household circles. At that time, not everyone was doing high school and regular college. They were in high school for about six years, and after high school they went to housekeeping school. There were special housekeeping schools for two or three years. My mother was in Sibiu. There they studied housekeeping. They were wives, and afterwards they were housewives.

I was friends with Imbroane's son, Bujor. Less with Doru (....) The Liberals made Bujor director in the ministry and he was a magistrate. Sorin Imbroane, the younger brother, was also a magistrate, he was a judge, but he was 4 years younger than us.

Horia Musta, born in 1914 in Oraviţa - excerpt from the interview conducted by Adrian Onică in Timișoara in 2002, Archive of the Group of Oral History and Cultural Anthropology, coordinated by Smaranda Vultur.

Sofia and Avram Imbroane House and Foundation

That is the purpose of man, to help, not to be selfish, and to live only for himself

All my other brothers were born in another country - allegedly - that it was not Greater Romania yet. The eldest was born in München, while my father and mother were studying abroad.

My father was an editor at Branişte's "Drapelul" newspaper, the editor-in-chief, and he went to Germany to study, and while studying there he wrote admirable articles, which he sent to Branişte's newspaper.

The second brother was born in Lugoj, when the provinces were still separate, the third in Bucharest, and a sister in Iasi, in 1917, and I in 1920, when it was Greater Romania… I was born in Timisoara. We were five children. My father was extraordinarily beautiful, he was an extremely generous man and he had an exceptional backbone, he was a man of great morality and patriotism. He also mourned the fate of women; he didn't want girls, but boys, because he said that women have a hard time in life. Boys were born, then my sister and they said "we'll find for her a husband", then I was born and they christened me "boy Ionică" and that's my name.

My father was the vice-president of the Chamber, immediately after the Union, because he fought for the Union and he was almost killed and judged by Hungarians and Serbs for the whole campaign he led. He escaped at the last minute, fleeing to the Kingdom.

He came here (in Muntenia) with his mother. In Căldăruşani he was a deacon, in 1914, and in 1916, together with Titulescu, Delavrancea and all the others, he fought for the idea of the Union. My father was a great speaker and he gave speeches. He was both a publicist and a great speaker, very talented… He was with them through campaigns to prepare the Union and that is how he became known.

Gala Galaction, who was in Cernăuţi when my father studied Theology (there he met my mother, in Cernăuţi) loved him very much. Delavrancea also loved him, he said of my father that he was "the nightingale of Banat", and also Arghezi loved him. There was no one who did not support him because my father did not want to become a minister, so he became a secretary-general at the Ministry of Cults and Arts, as it was called then. As secretary-general, he supported everyone and sought to do the impossible, to finance them and to help them.

In what year was he secretary general? 1933 -1938, because he died in 1938, as secretary-general. He lost my mother in 1933, she died suddenly at the age of 47. My mother also had splendid activity work in the public realm. She was the president of the Association of Women and Housewives of Timisoara. She made a school, the Housekeeping School(Şcoala de Menaj), and she brought peasant women from the countryside. She had to get that big, columned building that now houses the Prefecture, which was built to bear the name of my mother, Sofia Topor Tarnovietzki, because they were ennobled by the Poles in Cernăuţi. In fact, they were called Topor, and they were yeomans from the time of Ştefan cel Mare.

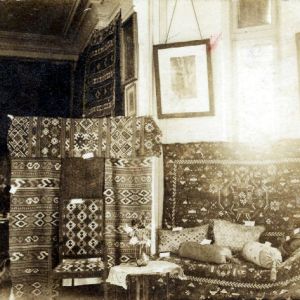

The school had to be named like that after my mother died. That building with beautiful columns had to be the building of the school for women, to do the social education for women from the countryside, that was her dream, to take care of the girls in the countryside. She was also a great collector of folklore, in love with folk art, and so she seconded my father in a way; for all her work she won grand prizes, in Brussels, in Barcelona, gold medals for her collections, which were lost during the war.

What collections? National costumes, embroideries, ceramics made in Banat, old Banat collars. She went from village to village and collected everything that was old and authentic and made a splendid collection.

In what year? Until 1933 when she died. She had a cerebral concussion and died at the age of 47.

Did she had a museum? She had nothing. She only had this collection and I tried after that, I showed these things… I don't even have her collection anymore, only partially, I have little left, because the majority was taken by a gentleman who said he was going and will deposit them to the museum, but I think he sold them abroad, he tricked my sister. She gave him 3,000 lei, a piece of cake at the time, and he said he will ensure this collection, and that's how he disappeared. There is very little left of my mother's collection, which can be seen on the wall, these are made of catrinţe (Romanian peasant homespun skirt) made by my mother, woven down, in our villa. There were women from the countryside who came and made beautiful carpets. She was a passionate collector. The president of the Women's Association was Queen Mary. My mother also took care of these activities with my father, having five children, but I also had an aunt and an uncle. My aunt, my mother's sister, who was a painter, was not married and took care of us, the children, and my mother took care of her public work. She was passionate about these ideas.

Was she born in Cernăuţi? Mymother was born in Cernăuţi in 1886 and her name was Topor. My father was born in 1880.

Did she live in Cernăuţi for a while? Well, all her childhood. Her father was the director of the Aron Pumnul high school in Cernăuţi, being a mathematics teacher. It was with tradition the Topor family, who came from Bishop Baloşescu, who was our ancestor. It was an old Bucovina family. My uncle was the director general of the Railways and was made, immediately after the Union, the Minister of Communications. They were people who were ennobled by the Poles for their professional merits. Many were ennobled there in Bucovina, and between them was also my mother's family. Tarnovietzki was added to the name Topor.

Dad had a splendid voice. Grozăvescu himself said that he had a more beautiful voice than his own, that is how splendid my father’s voice was. He went with the choir to sing for Christmas, met my mother, and fell in love with her.

What choir did he go with? With the choir from Bucovina, of theologians, because he was a student of Theology. He graduated in Theology and Law. He then studied law abroad.

How did he get to Cernăuți from Banat? Well, he went to Cernăuţi to the well-known Faculty of Theology, even Gala Galaction studied there.

Was your father born in Lugoj? My father was born in Coştei, in the Yugoslav Banat, and then my grandparents came to Vărădia. My father especially supported those in the Yugoslav Banat then. After that he went to Cernăuţi as a student, then he came to Lugoj, to Branişte, he was the editor of the newspaper "Drapelul" and from there he was sent abroad, to Germany, to study and to get his doctorate.

He went there on a scholarship, he studied with great sociologists, and sent thundering articles from there. I have his articles, which a gentleman Rădulescu from here, who went to prison, told me he would publish, but everywhere money is demanded, and I couldn't get enough money to finance it myself. I. He wanted to publish all of my father's articles, which are wonderful.

Did he write memoirs? He didn't had time for that. He always fought for all sorts of national causes, but he didn't write about himself… He was very modest. Because he was a deputy for years and was the vice-president of the Chamber, in our house was a long line of people who came with requests.

Was he a Liberal? Yes. Brătianu became prime minister, because he was called to Paris in 1919 to present himself at Wilson, and there he almost convinced them with his oratorical talent to give up the part of Yugoslav Banat that we lost, including Coşteiul. Then things changed here, the Bratians came to power, the policy changed and they returned from Paris. That part was given away and the border remained, which was extraordinarily painful for my father, because that whole part, so beautiful and with such well-trained and good Romanians, remained in Yugoslavia. And then my father continued to support them as much as he could when the Liberals came to power.

In what year was he a deputy? He was a deputy right away.. He was the vice-president of the Chamber, immediately after the Union, and then he was a deputy whenever the Liberals were in power. He died as Secretary General of the Ministry of Cults and Arts.

In what year did your father die? In 1938. I can't thank God enough that my father died before he went to prison, because he would've ended up in prison, and you can imagine how much he would have suffered for him and for us. After all the life dedicated to this nation, to end up imprisoned, as so many other people had been.

(...) At that time, my poor mother was left alone in Iasi and woe to her for living with four children, one of whom, my sister, was born there. A year later she was told that her husband was not returning, but the poor man returned a year later, stealthily between two wagons. Then, from Iasi, he left by plane and organized the Great Union from Alba-Iulia. He was one of the organizers of this holiday. I have the words from the secretary of the General Assembly who said what a fulminating speech my father gave on the eve of the Union because there were people from Banat and Transylvania who demanded autonomy. Even Branişte supported the autonomy of Banat, but my father was against this idea, he supported the unification of the whole country and then he gave a speech that had an extraordinary effect, it seems, on the eve of this Great Union. After that he came to Timişoara and he was either in Bucharest, as a deputy, or in Timişoara, where he carried out his activity.

I was born in 1920, in Timisoara. In 1920 the family was already in Timisoara.

The editor-in-chief of the newspaper "Banatul" was Camil Petrescu, who adored my father. He wrote some admirable things about my father, that he understood him, he understood my father's soul, almost mystical, my father being an extraordinary idealist who lived for the idea of Union.

When the Dr. Avram Imbroane Institute of Romanians across the borderwas founded in 1934, he gave a speech that I have written here between these articles. He gave a speech about the lack of solidarity of the Romanian people. For my father, this was one of his greatest sorrows, when he saw how little solidarity the Romanians showed. It's a birth defect of theirs that continues today, as you can see. When one stands up, instead of supporting him, on the contrary... And it hurt my father very much and he wrote some admirable things, some very beautiful articles. And then he wrote against politics. He wasn't a politician at all for the sake of politics. He became by chance, fighting for this idea, then he became a deputy and so on, in the liberal party, that he was with Brătianu, but he didn't love politics at all, but it's true that he was a politician's head, that is to say he thought well politically, which today you rarely find. Poor father...

Did he buy the house? This house was bought by my uncle and aunt from Cernăuți, who were not married. My uncle was a railway general manager and my aunt a teacher. The other aunt, a painter, was called Maria Topor Tarnovietzki. All the paintings were made by her. She had a very successful exhibition. Stoenescu appreciated her enormously. She started painting when she was 35 years old, and she was painting with passion and took care of us. My uncle and aunt gave money and bought the house because my father couldn't afford it. They bought the house because they didn't have any children and then they said that Sofia, my mother, that's what they called her, should have a house with a garden, because she has five children. My mother dreamed of having a garden.

Do you know who they bought the house from? From a gentleman who was a bit broke, I think he was playing cards or something, and had to sell it at an affordable price. He bought it in 1929. Trouble was, it was half and half on the land registry. After that it was sold at an auction and at one point, we were about to lose it. During the war, I don't know how it happened that we were about to lose it. Eventually the amount was paid, and it was clear that it was our house, number 14, and Franzen the German's house, number 16. (...)

I was born in the apartment that is now my brother's, at 1 Ion Ghica Street, opposite the former Notre Dame High School. There was a house on the corner with a tower, there were four apartments of four brothers. Downstairs was Strumper's fur shop and three stores.

(…)

What high school did you finish? I finished in Timisoara in 1938, and in 1939 I went to Paris, because I had my brother Doru there, he had his doctorate. He was exceptional, this brother, but he died at 27 years old, at the beginning of the war. He was exceptional, he took three doctorates at Paris. I was there for a year with my sister and then I went back and did Fine Arts.

Did you study there? I mainly studied decorative arts.

In what city? In Lausanne. My poor brother came here in '40 and then died here. We came back a year later because the war started. I enrolled at the Academy of Fine Arts to please my aunt, who was a painter. I had a talent for portraits, but I wanted to study a lot of things and, apart from the Academy of Fine Arts, I then studied Literature, especially History of Art, I studied with Oprescu for four years.

(…)

Did you live in Timișoara until you finished high school? I finished high school in '38, and in '39 I went to Paris. In '40 I enrolled at university and in '42-'43 I went to Munich to study.

Were there some scholarships? No, but you know how cheap it was... In Germany I lived cheaper than if I had lived in Bucharest. There were special conditions. I went to a hostel where I became friends with different girls from there, and even now, I’m still in touch with some of them. It was a girl students’ hostel. I stayed there for a year and then the bombardment started, and they wouldn't let me leave, so I stayed here and finished my studies.

What was life like in Timisoara when you were in high school? As it was, life was beautiful. There wasn't as much cultural activity as there is now. Now, Timisoara has become much more cultural these last years. At that time there was less cultural activity, but my father supported it, supported the theatre in Timișoara. In fact, he also supported it in Lugoj, being the editor there, he supported the actors in Romania. One of the actors, Leonard, said that no one has done as much for them as Avram Imbroane did through the press, that he wrote articles about theatre and supported Romanian theatre enormously. He considered it important on the cultural line.

With whom were you family friends in Timisoara? I had many colleagues, Ligia Montane, who was married to the prefect. The Gomboșiu family, I knew Valentina Pintea. I had an uncle in Timișoara, Ion Imbroane, who built the church in Iosefin and who was a religion teacher at Carmen Sylva and who was also my teacher. But he didn't give me the highest mark, he gave me a 9, to show that he doesn’t make a difference because we are family. I went to Carmen Sylva High School, which was an extremely serious high school, and when I finished, I knew French perfectly. (....)

I became a technical drawing teacher in Bucharest, for one year at the elementary school, then at Cantemir High School and then at Spiru Haret. Recently, I even met some of my students. I had Radu Gabrea, who was my pedagogy teacher at university, and his children were my students. Professor Dr. Bruckner was my student at Spiru Haret and even the mayor of the 2nd sector here in Bucharest, Popescu. I met him ten days ago and he told me: "Mrs. Crăiniceanu, I'm talking to my brother who is in Cologne about you, about what a teacher you were, what an education you gave us...". I was very much involved in the artistic education of children, and I tried a lot, in my classes, to give them artistic education. I loved teaching. I tell you honestly, I didn't want to become a teacher, I wanted to become a researcher, but I was passionate about this contact with students. (....)

Did your aunt take care of you at home? My aunt did mostly, because my mother was too busy with her chores. She was observing me while I was studying piano.

Who was cooking? We had a cook in those days. That's all I can say, poor as we were, because we weren't very rich, we could afford to have a cook. The only thing I envy my mother for now because I hated cooking... It took me half my life to prepare food, so I said look, poor mother, she could afford to have a cook.

Did your mother establish the housekeeping school? She did, with Queen’s Mary help. I have photographs of my mother and Queen Mary. She established it, put her heart and soul into it and brought in countrywomen from the countryside who were trained at this school. She had great ideas, she wanted to achieve a lot, but unfortunately, she died so young (...)

We grew up very nice and I had very conscientious brothers, values, serious people. Brother Bujor, who I said was kicked out of the judiciary, suffered because of his name. My father did nothing but good for the country, he wasn't rich, he didn't have a fortune, he had nothing to be judged for, but the communists judged him because he had a name. (...)

Who was Nicolae Imbroane? My father's brother, who was a lawyer and prefect in Timișoara. He is the grandfather of this girl who helped me with the foundation in the beginning. Nicolae Imbroane was taken to Bărăgan.

Was he raised in Vărădia? Yes, he was for a while and then he died quite quickly.

Does the house from Vărădia still exist? I don't know. It used to be our house, but I think it's gone. The Brătianu family inherited it because we are related to them. My cousin, Nicolae Imbroane's daughter, married a Brătianu. Delia Imbroane was a very beautiful girl. She went to high school in Timișoara and married Radu Brătianu, nephew of Dinu Brătianu. Her children, one of whom died, and the other is a teacher in Câmpina, inherited this grandparents' house in Vărădia.

They were Brutus, Delia and Titus Imbroane, who had Latin names and were the children of Nicolae Imbroane. And my father was careful to put names like that, so they couldn't modify it according to the structure of Hungarian language. Here, they were called Bujor, Doru, Sorin Nicolae, Dora Romanița and Steluța.

Titus Imbroane stayed in Bucharest? He studied law in Cernăuți and lived in Oțelul Roșu. That's where Titus' family is. Brutus Imbroane's daughter is Cornelia Rădulescu, who is in Timișoara.

How come your uncle was from Vărădia? He was a lawyer, but he left the law and went and built a mill there, having a piece of land from my grandfather, and he liked the country and that's where they took him from.

(...) My idea now is to support especially those from Chernivtsi, because those in the Yugoslav Banat are living better. I don't know what the situation was like, because they have links with the Romanians... Those in Timoc and beyond are doing badly, but those in Bukovina are doing terribly. Tărășteanu, a journalist, came to see me and didn't know how to hug me when he heard that I want to give them money. I also spoke to Mioc and Orban, because I wanted to host the revolutionaries in my villa. Then I gave up, because he gave them a big house I don't know where in Timisoara. The idea appealed to me, because I had that enthusiasm, since then. Ana Blandiana spoke directly to Orban, that Mrs. Crăiniceanu wants to give and doesn't succeed...

(....) I have a cult of the dead and I made an admirable grave for my father in Timisoara.

Where is the grave? In Calea Lipovei, as you enter there is a chapel and next to it there is a tomb with a double cross made by Anghel, a great sculptor here. Downstairs is the tomb where my whole family lies: my father, my mother, my brothers, and two tombs further on is the tomb where my aunts are. I also brought the graves of my grandfather and my aunt to this grave, where my husband is buried and where I will also be buried, my name being written there. A grave separates us from my father's grave. It says Petre Crăiniceanu, and on the other side it says the names of all the dead, including my grandfather Mihai, on my father's side. They never found my grandmother. (...)

What do you think is important in life? To achieve something, so that something remains after you, that's important from my point of view. To achieve something, not to vegetate. To fight for a cause. I also look at people who support children, because I have friends who take care of orphans. That's a nice idea, and it should be supported. That's what you live for, to do something, to help people. I inherited that and I don't like to brag, I don't like to talk about myself, but when I can I do good, I help people around me that I see need help, with advice, with what I can...with doctors, because I know many doctors who love me and took care of my husband and when I can I help people. That's the point of man, to help, not to be selfish and live only for himself.

My father was like that. To have dared one of all those people who came there, when he was a deputy, to offer him a chicken, that he was gonna send away from the door, because it wasn't in those days to come with bribes and gifts. He was doing it because it was his duty to do it, as a deputy, to support people if he could.

Did he accept them in? There was a line out the door until on the street. There was a line of people who came to see my father to support him in Parliament for various causes. ...And then I came to give a bribe to a magistrate, to earn my inherited fortune from an aunt, which was not a fortune I don't know how big...a fortune there. What a terrible time we live in!

I've never been envious in my life. I've never suffered from that disease, and I've never suffered from jealousy, thankfully. My only envy now is of those who have died, that they have escaped this mess of a life that unfolds before our eyes. Because all this politics is such an awful mess, I can't say.

We have suffered so much from communism, so much misery has communism brought to the world, to all these countries! Can't you see that a country is not progressing properly, and ours is in the lead. Albania and Bulgaria have overtaken us. Then how can I be happy. God, I'm so happy my father didn't live, that he didn't live through the communist era.

Do you know any of the people he was friends with? It was the Jew, Löffler, who was a great photographer in Timisoara. His father was at our house all day. My father also had Hungarian friends, but he made no difference between them. Of course, the interests of the nation came first, but you were not allowed to persecute minorities, there was no such thing. You can see that in all his articles. That's why he was so beloved. Even Maniu, and from other parties, everyone respected my father. He was a man of rare cleanliness and beauty of soul, and not because he was my father.

Were you close to your father? Well, of course. He was such a beautiful soul, he was exceptional. (...)

Steluța Crăiniceanu-Imbroane (born in 1920 in Timișoara) interviewed by Smaranda Vultur, in 1999, in Bucharest - Excerpts from the interview published in Dr. Avram Imbroane, Political Will, , 1st edition, Ed. Marineasa, Timișoara, 2003, Preface by Constantin Jinga, Foreword by Mihai Șora, Chronology by Remus Jurca-Unip, In memoriam by Horia Musta, Edited by Adrian Onică and Roxana Pătrașcu.

Female Portraits in Timișoara sec. XX - Ep.1: Sofia Imbroane, video by Claudia Tănăsescu

Link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qe26mU_DRc0

(...) Unfortunately, when I was born, one of my grandmothers, my mother's mother, was no longer alive. The other grandmother lived in Hungary, in Pécs. In the summer I used to visit her, but that was about it. So I wasn't really together with my mother's family or my father's family. My mother is of Austrian origin, she was born there. My grandfather was a doctor. In fact, my grandmother separated from my mother's father and remarried this doctor, my grandfather. My mother's father wouldn't leave them alone, he kept harassing them and then my grandfather decided to go to Homokos (Nisipari), where he was a community doctor. My parents met there. My father was from Baranya, in the Pécs area. My father was a notary in Kevevara. I was born there in 1905, on June 21. I'll bring the map to show you where Kevevara was, near the Danube, near Belgrade.

Tell me about the war. Did you know any Germans who were taken to Russia? Yes. I had friends, who then went to Germany. My friend was taken to the mine and a pillar fell on her leg. She suffered a lot. When I went to Germany with her, she was sitting hard on the armchair with that foot. She is still alive and one more, that's all. They took many. Hungarians were also taken from Brasov. Tell me. Here in Timişoara, in ‘44 I think it was, or at the beginning of 45. My family was moved from the house to an apartment in the building across the street. Here, in the house, was the headquarters of the Russian army that gathered the Germans. And the Romanian army was up here. From the city they brought the Germans here and rode them to the Small Train Station. We were looking out the window. And then we went home.

What did you think about what was happening? Well, we were all sad and worried. Because the Germans and the Hungarians lived very well together. And so did they with the Jews. No one here has ever asked you what nationality you are. There were no differences in Kevevara either. They also took the Hungarian prisoners. There was a factory here nearby, where about 25, 30 Hungarian prisoners worked. Their boss, who was an officer, was not working, and we befriended him. Horwáth Iános was his name. He used to come for lunch and we got along very well. One day he called us to say that if we still wanted to see him, to say goodbye, we should go to the Children's Hospital. He said they gathered them there to send them back home to Hungary. But they did not take them home, but to Russia. (Did he write to you later or how did you find out?) Yes, he wrote to us from Budapest. He thanked us for treating him so well. He and his wife invited us to visit him. That was in 47.

(...) That's how I made the will that until I live, I want to be alone in this house. When my mother was still alive, the third room was taken from us. There was that problem with houses and they brought families of three, four people here. For two, three years some stayed and then they brought others. We suffered very, very much because of that. They used to tell us: "You old women, I'll throw you out! This place is ours!" They were beating us. We suffered enormously, enormously! And that's why I said that while I'm alive, I want to be alone. I could rent that nice room in the front, but I won't. I can't stand living with a stranger. We didn't have the guts to go into the kitchen, we didn't have the guts to go to the bathroom, they'd attack us. They took the kitchen table and took it to the stairwell. How much we endured... I suffered so much I can't even tell you.

You have a very nice house. It's beautiful and it's very practical. Many things I have already sold and many things I have given as gifts. Renatta, my best friend's daughter, I gave her a leather lounge set, she took it to Germany. I also had furniture, couches, all kinds of things, but I sold them when foreigners came to the house. (...)

Pintér Sarolta, born in 1905 in Kevevara - excerpts from the interview conducted by Antonia Komlosi in Timişoara in 2003, The oral history and anthropology group archive, coordinated by Smaranda Vultur.

The Pinter Sisters

Tonight, the Pinter family. Șari and Ghizi. Two sisters. They lived with their mother, in the apartment with the left side balcony. They were living almost alone in the big apartment. Almost, they say, because in a separate room lived Mr. Rosca, a much younger single man, who later became for a while Șari's husband. For a long time, their house was a place full of mysteries for the child I was. First of all, their apartment was separate from the rest. They had a wooden lattice door on the balcony, which was closed with a quarter turn screw, a sliding system whereby a small metal tongue, fixed to the hinged side of the door, slid into the fixed side. To get in, you would have to be tall enough to be able to put your hand through the door... I wasn't big enough, so I'd reach up to the front of the gate and peek through the wooden bars to see Ghizi neni's grey cat, maybe-maybe she'd appear in my sights. I didn't get into the house until a couple of times later. We sometimes had access to the large kitchen where the three women spent most of their time. The kitchen could be seen from the outside, however, when we sat on the balcony in the opposite corner, on the other side of the "U" on which our lives flowed. From there, I carefully researched the daily ritual of the preparations. The two younger women worked together, assisted by their mother, seated at the square table covered with moss. But nothing was more precious than the moment when the cakes were being made. Aunty's guide would lower the glistening, green-painted wooden cupboard, the gleaming brass-metal vessel, like a large half-ball. In it they scrambled the eggs, whipped the foam. On the little stool in the corner of the kitchen, I had the privilege of watching the show a few times. I didn't know which way to look: as in a ballet, perfectly directed, each of the six hands performing, in silence, mastered the score perfectly. On one side, the yolks were separated and mixed with sugar. In another, from the viscous liquid, left to flow when the egg was cracked, white foam, like snow, swelled and could stay in the air without falling... The order did not allow for any exceptions: from the pantries that lined up in front of me, Shari would pull out truffles that I had never heard of: figs, browns, raisins, golden, walnuts... Back when the only dessert I had access to was marmalade that was cut into cubes at the corner grocery store, auntie Ghizi had secret reserves of real ingredients from which they carved the illusion of normal time. They had been notary's daughters, it was rumoured that they still had a fortune, their house, closed off to new neighbours, brought in with an allotment, hid the old joints from which they had been torn. We, the Ianovici girls, were somehow tolerated. Just Renate's playmates, whom the "old ladies" took care of. We had only known Renate's father from the picture on the wall, and auntie Roji was missing from home. Kurti - the older one - and Renate, about Carmen's age, only a year older, were looked after by the Pinter sisters. Renate ate there and then we could go too - I had my place on the little stool, almost unseen. When the protocol of the birth of sweets was over, we would receive a few slices of cake on a plate of painted fruit. In the Pinter house, with the saucer in my hand, I heard names whose sound carried you far away, to places where food was made in a ceremonial way that was spellbinding, where the gesture of putting it to the mouth was measured, and tastes were delicately placed in the concavity of the mouth. A little later, when I learned to read the little books with the figure of Piticot on the cover, and I arrived where the prince invited the princess to dance, in the great ballroom, I knew that on the table between the columns there must surely be, on silver trays, the slices of "zserbo", with the state of dark chocolate on top of that of dough and walnut, and with the sour taste of jam between them, or the slivers of jasper, thin and fine, or, if she proposed, I knew for sure that the princess would end up eating the cake and trying her teeth in the strength of the caramelized sugar glaze. ...

Auntie Ghizi spoke Hungarian with Renate and when Renate was crying she would take her in her arms and call her "my baby". Nobody called me “my baby”, but my mother was not in prison, as I heard Renate's mother was. But I didn't quite understand why Renate was crying that her mother was there, when she must have been fine - I heard she was with all sorts of ladies who were friends of the Queen. Many years later, when I was already grown up and went to visit auntie Müller, I found her writing, her beautiful handwriting gliding into scrolls. I asked her who she always wrote to, and she told me then that she had many friends with whom she had spent several years in prison and that she wrote to those friends. I even met one - it was Frida Holban. She had come with Mircea, her husband, to say goodbye to auntie Roji before they left for Switzerland. Mircea had a castle there, as I had heard. I had never seen such a lady before. She smoked with a snuff, long cigarettes and wore a hat with a veil. I learned a lot from auntie Müller, but that's another story.

I don't know when old Mrs. Pinter died. I only remember that I had access to the rest of their house then and saw the "treasure" I had longed for for years: the large, heavy, red marble-panelled dining room and the beautifully carved cupboards. More impressive, however, than the exterior furnishings was the richness inside. On the large dining room table - which had, on that occasion, opened out, growing larger, Roji Auntie began to remove the heavy, silver crockery and cutlery from large wooden boxes. Then crystal glasses, gleaming. I was so impressed by the signs of their well-ordered life that never since then, seeing the thick, white china everywhere I could buy it, have I been able to suppress the desire to gather it up, to place it carefully on the cupboard shelf, to take it out, to plow it, a sign that life still has its place, that Sundays can still smell of peace and cinnamon, that the weather has not broken and the joints have not perished.

We moved from the second-floor downstairs to the ground floor. I was already grown up in high school. I didn't see the Pinter ladies anymore. Șari went for a long time, to Vinga, to Pencoop, from where she brought eggs sometimes. The cakes were probably just as good. We, however, went to the bakery from now. We used to eat juciy savarins.

My mother used to make zserbo for Christmas, according to auntie Gizi’ recipe. But we preferred savarins, which we were eating with the boys at the bakery...

Then we left. A few years ago I read in the newspaper that the town hall had sent a delegation to Zürich Street, where a woman who had just turned 100 lived.

Auntie Gizi.

Sorina Jecza - 2 Zürich Street – 12 July 2015

The place where I've always known. With the distances getting shorter as the years went by: the way to the Little Railway Station, from where my mother "gave us in the care" of a relative, to take us to Maichi, to Izvin; or the way alone, to Telegrafului Street, where Auntie Ani was waiting for us at the kindergarten. With Carmen by the hand, with the little metal bag, where my mother would feed us. Then, a little across the street, Marica Sârbulescu's house, where my mother would drop me off to play from time to time. Their big yard with chestnut trees. Marica, frail and skinny, silent. Sachs Otto Eugen, more sure of himself, protected by his older sister Rita. I still meet Marica in the market. She always gives me wreaths for the dead at a discount. She wraps her shawls in a thick sweater - it's so common in this market - and doesn't say a word. I don't know anything more about Sachs Otto Eugen. I'd heard he'd left for Germany a long time ago, Rita and all. Telegraph Street has widened. It connects the old Fabrik area to the city. I must go there one day, to see the hotels that have sprung up everywhere...

On Zürich Street we were feeling like we were abroad. The whole neighbourhood was outlined on the eastern edge of the city, right near the train station - the Little Station, as we were calling it. The place was actually the city's link to the surrounding villages. The fantasy of I don't know which mayor, however, dreaming of Swiss neutrality, brought here cosmopolitan-sounding street names: Alsacia, Lorena, Zürich, Geneva, Basel... They came out of Kogălniceanu, a wide street where tram 2 used to pass, the one that made the glasses in the shop window vibrate at every passing by. Among the streets of the small neighbourhood, the great men of national history - Mihail Kogălniceanu, Samuil Micu, Simion Bărnuțiu - peacefully intersected with a domestic Europe, which was fending off the fences, the lilac and forsythia bushes.

Our house was right in front, on "Zürich, corner with Kogălniceanu", as we were to give the reference point later, when we were driven home by knights in taxis. In the back, almost a village: after Ocsko Park - the park of the Sock Factory, as we called it, of the Kimmel family, as it had been, in fact - the streets lined quietly with modest, clean little houses. A world in which grandparents had not had their possessions taken from them, for they had not, but which retained the patriarchal quiet of a settled world. Yards of cherry and horse-cherry trees, which blossomed in spring with a promising, beginning scent. From these houses came, later on, our colleagues - Cornelia Țeicu, from Renașterii, Rodica Garofeanu, below, from Zürich... They lived there for generations. Most of us knew their grandparents. Others were more recently settled here: they had moved to the "new block" at the end of the park: Gelu Drăgoi, with his sister, Luminița, who became a dentist, then Pupa, whose Italian lover had died years later in bed, making love, and when the whole neighbourhood was watching how the cops were going around to discover everything... They, the children from the block, came more often to our yard, to play "countries", because they lived in the rooms of the block, where they would crowd with dad who wanted to smoke or mom who would put them to work. ..

We were on the corner: an old two-storey unit (when the unit next door was built in the 1960s, they had made the same height four storeys high, to fit the people better!). With windows facing the street, on both sides of the unit - one side on Kogălniceanu Street, towards the tram, the other, where the entrance gate was, on Zürich. The windows had esslinger uri (I don't know if the name of the wooden rollers that protected us from the heat of the hot summers comes from the name of the designer at Apple; they were, however, definitely of German origin, being too good!). The whole unit had been built house by report by the Kimmel family. The tenants were of more recent vintage, crammed into large, generous apartments, two to three families. We had been given two rooms upstairs, on the second floor, in apartment 11. I only vaguely remember what it was like before my parents did the "breakdown", the great revolution that was to bring us the added comfort of separate living. When they moved from Reșița, where I was born, during the time my father worked there, the four-room apartment housed three families: the Homeag family, the Toma family and us.

We had the rooms facing the street. In the first one, my mother's furniture, a wedding gift, made at the Fântâneanu workshop, made of walnut wood, curved, with a crystal display case in which the glasses that were not taken out all day were kept. It was a model of so-called "combined" furniture, a sign of the mixed times, too: with a tall wardrobe, to which was attached the body corresponding to the living room, a little shorter than the wardrobe part: a narrow glass case, at the top, under which in the middle the "bar" - with a door that descended horizontally, turning into a kind of small table. With its mirror-lined interior, the bar was held for the few bottles where my mother put the homemade cherries and eggnog, in which I would have liked to dip my lips a little, so appetizing was it - thick, honeyed, sweet, as I had tasted it on the rare occasions when I "cleaned" the leftovers on the little cups, from which, with almost piety, a little was served to guests. Under the bar were a few drawers, chubby rounded in shape. The last two held the family history: land registers, dowry deeds, birth and death certificates, as was the custom of the time. That's where we started to look, late, when we were reconstituting property, for the documents we still needed at the court. To the side of the bar was a second, wider glass case, under which another set of doors, two in number, opened from the middle, to leave three wide shelves, on which stood arranged, horizontally, the treasures we longed for...

Sorina Jecza (in End days and other days) - 16 February 2017

Today we tried an old doorknob, almost forcing it: we walked together down Zürich Street to number 2 - our childhood home, not seen by Carmen for more than thirty-five years. We'd been piecing together the stories of the house over the past few days, but we'd stumbled in a couple of places: who the Kappler family on the first floor shared their apartment with, and what they called the blind men weaving brooms in the basement, in the courtyard apartment. We weren't quite sure about Mrs. Gulyas either - the gully, as she later came to be known to the new tenants from Oltenia. I hesitated, at first, between Gombos and Galambos... For the rest, they all came out - the Pinters, the Welthers, auntie Erhan, Ada and Caesar Ofițeru, and the Wechslers. And Klein, and Peia, and Bucur, and Müller, and us Hanoverians...

The house on Zürich Street - a benign little Switzerland, neutrally divided between Jews and Hungarians, Romanians and Germans, Gypsies and Serbs... bound by the same poverty of an equalizing time. I left from there in 1982. I was 27 years old.

How many stories to tell there have consumed their mystery... how many to hide...

I spent three hours there today. Our interlocutors - the shadows of memories, the trees in the park - the huge maple and chestnut trees, the walls - narrower, smaller, the mosaic of corridors, on which we jumped the shallot..., just as beautiful, with its curving, undulating, flowing lines, like a musical leitmotiv.

Sorina Jecza