Traian Square, 3-4 Traian Square

"Traian Square is the central square of the Fabric district, its beginnings being related to the first half a sec. in the 18th century. The original appearance of the Square was very different from today, given that many of the existing buildings at the time were relatively modest, with a single level and a rather rural look. The current appearance was received only at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, when the great palaces were built on all four sides of the square."

Listen to the audio version.

Traian Square (formerly called Kossuth tér and Hauptplatzis the central square of the Fabric neighborhood, its beginnings being linked to the first half of the 18th century. The initial appearance of the square was very different from today, given that many of the existing buildings were relatively modest at the time, with a single level and a rather rural aspect. The square was the place where the weekly fairs were held in the past. The current appearance was received only at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries when the great palaces were built on all four sides of the square.

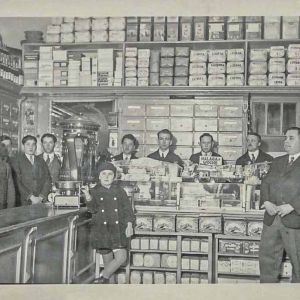

The Serbian Orthodox Church, dedicated to St. George, located on the eastern side of the square, was built between 1745-1755, being one of the oldest buildings in the entire neighborhood. On the left side of the church, at the end of the 19th century, the House of the Serbian Community of Fabric was built. Edified in the eclectic style/historic style, the building housed on the ground floor many famous shops of the time, among which we recall the Csendes shop or the Kohn brothers store.

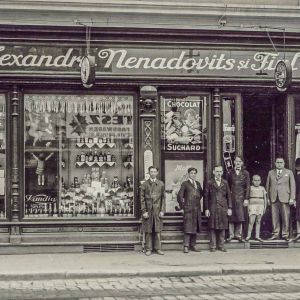

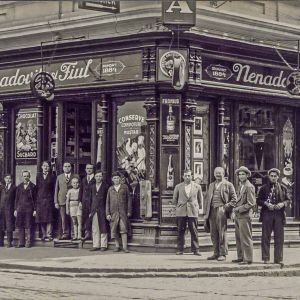

On the northern side, named after the original owner, Bela Fiatska Palace or the Mercur Palace was built at the beginning of the 20th century. Edified in the Secession style, the palace has a distinctive ornamental element, a bronze statue of the god Mercury, located on the corner of the building and the Square. On the ground floor of this building was the shop of the merchant Al. Nenadovics.

The western side of the square also hosts an impressive palace, the Palace of Countess Ana Mirbach, built at the beginning of the last century in the Secession style, according to the plans of architect Josef Kremer.

Among the houses located on the southern side of the square, the building once owned by Baron Mihai Nikolics of Rudna stands out.

There are also two public monuments in Traian Square: the obelisk or pyramid with a cross, erected in 1774 by the senior official from Timișoara, Stojša Spasojević, and the stone bell, the work of artist Ștefan Călărășanu, erected in honor of the 1989 Revolution.

Bibliography:

- https://heritageoftimisoara.ro/cladiri/Fabric/adresa/Traian/2 site accessed in May 2021.

- https://heritageoftimisoara.ro/cladiri/Fabric/adresa/3+August+1919/33 site accessed in May 2021.

- https://heritageoftimisoara.ro/cladiri/Fabric/adresa/Ion+Mihalache/1 site accessed in May 2021.

- http://ploaiadecuvinte.blogspot.com/2012_04_13_archive.html site accessed in May 2021.

The Traian Square

I was three years old when the "Excelsior" Azur factory, varnishes and paints, where my father was a shareholder, went bankrupt. (…) And then they thought, my father thought it would be good to start a Serbian newspaper, because there were so many Serbs in Banat and they would surely have subscribers. And so, he did. They founded this newspaper (Temisvarski Vesnik, 1933). He found a pressman in Cetate, on Eugeniu de Savoia, where there was a printing house that agreed to print his newspaper. The newspaper was biweekly, appearing twice a week. He had apprentices who came from the countryside, a little smarter, who wanted to become pressmen. And there were two couriers. The manuscripts were written by hand, at our home, first there on Samuil Micu street. And from there they came here to the Cetate. I don't even know how those kids came there, by tram or... And the proofreading was done twice. First the manuscript was collected, a sample smeared with printing ink was drawn, on which the corrections were made at the edge, that it was made on the slits. Even then the corrections were made at the edge, with signs that I still remember what they looked like. And then the courier would run back with them, correct them, do the second test, and run home again, and only then would it be good to print. And someone else was going there to do the proofreading, they were doing another page, a trial page, to see if there were any gross mistakes. So, the third correction was made there. So that was Monday and Tuesday until noon - you can imagine how fast they had to be there! At noon on Tuesday, the newspaper was being delivered. And for that, they had to stick the addresses on every newspaper. I don't know how many subscribers there were - a thousand and something - two thousand subscribers in the whole area, all the way down to the Danube: Arad, Timiş, Caraş - they were villages with a lot of subscribers. And by the end of the year, they were starting to gather material for the Calendar.

(…) What did your childhood factory look like? Ah, the Fabric of my childhood was very beautiful. I also remember the shore of Bega, where I played and fought with my cousin, who is only a year older than me... When we moved to Traian Square, we lived in this part where there are household items and they lived at a right angle, in their house, which was Nenadovič House - it was only one floor high, but the roof was very high, and downstairs were all kinds of beautiful shops, and in the corner was grandpa's shop. "Nenadovič Alexandru şi fiul " What kind of store was it? It had delicacies, a Grocery shop and Delicacies. What a craziness! All the good things in the world were there!

Xenia Manojlovic, born in 1930 in Timișoara - excerpt from an interview conducted by Simona Adam in Timișoara in 2002, The oral history and anthropology group archive, coordinated by Smaranda Vultur.

I remember a small episode, which may be of interest to someone who wants to know Timisoara, that a certain merchant, who had a small shop near the Power Plant, on Ștefan cel Mare, wanted to move to Traian Square, because there it was a free space. He came to my grandfather, because he was the oldest of all the food merchants, because there were five of them there, and he asked him, "Mr. Nenadovici, look what I'm thinking... Do you agree for me to move to Traian Square?” My grandfather told him: "Yes, sir, move!" Commercially it was not a competition, because it was a small company. Then he went to the other patrons in Traian's Square to ask them: “Gentlemen, look, I went to Mr. Nenadovici's and he agreed for me to move here. Do you agree?” "If he accepts you in Traian Square we agree." I'm talking about the ones from the food industry. So, the man did not simply come to rent the space because it was free and ready, as it happens today. That was the atmosphere back then and it was a very light, a very relaxed atmosphere. People got along and it wasn't a clientele that was just Grosz's or Toth Sandor's or Katz's. The dispute at the time was simply commercial, through what you could offer. For example, someone from Bucharest would come to my grandfather and say: “Sir, I brought a sample of the original rum from Cuba. Taste and tell yourself how much you want to take from us ". My grandfather or my father, who knew how much is sold here every year, because the rum in Cuba was famous, talked and told him that they wanted this much quarterly and and this much annually. For this, the company offered exclusivity, meaning that in Timişoara it did not sign a contract with anyone else. Those who heard, after a few months, that this company has rum from Cuba, came to buy. Of course, that was what attracted him, but they would also buy something else since they came into the store. That's what those merchants did. This was an example with my grandfather and my father, but so did the other merchants, with other items, which they had exclusively. (...)

But they were very good people. Because my grandfather was a merchant, he wanted his son to be a merchant too, and that's what he did. My father did the whole hierarchy, starting from apprentice, from calf, as these trades were called. My father was my grandfather's companion, because that was the name of the company "Alexander Nenadovich and Son". My father then took over this firm from my grandfather, and continued. While my grandfather was alive, he was always in the shop, more honorary, because he was old and already weakened by his strength.

Vladimir Nenadovici, born in 1923 in Timișoara – excerpt from an interview by Adrian Onică, Timișoara 2003, The oral history and anthropology group archive, coordinated by Smaranda Vultur.

I lived in an area where poor people lived, a Jewish neighborhood. The Fabric neighborhood was a neighborhood of Jews, Neologicals, Orthodox and Spanish, there were many, thousands of Jews were here in Timisoara and all these religions were freely practiced wherever they wanted. For jews, there was a restaurant named Koser located in Fabric, it was a church, a big and beautiful temple, but today you can't even see inside because people are afraid that the ceiling might fall.

On Friday, the Jews would take the sweet leavened bread (in Romanian it is called “cozonac”) to a baker to bake it because in the evening the cozonac was cut and they were praying, Brohe prayer was said, the one in which you thank God on Friday night. They would take all of it to the Orthodox bakery, there was a restaurant with free access, everyone could go there for a meal that avoided foods that were forbidden. It was beautiful when we went to that synagogue. They were beautifully dressed women, the rich showed off all their jewelry, and we all always received new clothes and new shoes for Easter. Gifts like this were always made for the holidays. Men offered bouquets of flowers to women, this was the day when it was Lent, you would eat in the evening and until the next evening when the stars appeared you didn't eat, smoke or drink anything. This is Lent, it is done for the salvation of the soul, or as they say, for the forgiveness of sins.

Were there Jewish schools? We had high school, we didn't have college and there were several schools in the neighborhoods. On the street where we lived, the Talmud-Tora was taught, the 7-year-olds went to that school and then they went to the high school that was in Cetate.

What was the name of the street you lived on then? Negruzzi Street, other streets where Jews lived were named after historians, scientists. We lived with many Christians and had a lot of children in the house. Well, now that Easter is coming, for example, we use pască (Easter bread), we eat that pască, but then from that pască the neighbors who were Christians would also eat, they ate for pleasure. They brought us red Easter eggs. We had a great time at Easter. I believe that in Romania the anti-Semitism has not reached high levels as it has reached in other countries neighboring us. We didn't hate each other, we didn't hurt each other, the legionnaires ruined the atmosphere a little. Only if I tell you what misery I lived in, there were so many children living in a home with only a room and a kitchen and there were a lot of beds and there was a lot of poverty. Often the children didn't go to school because they didn't have shoes. Poverty was severe, and only poor Jews lived there. Now, it seems awful to us to live in a block, but back then the people who thought they were rich and wealthy and had everything, they were actually middle-class Jews. They weren't extremely poor, but they weren't wealthy either. Now society has developed and so have we. We are originally from Spain, we are called Mangelus, we are Sephardic, the Romanians call me mangeloaică.

Kornelia Mautner, born Benjamin, in 1920 in Timişoara - Excerpt from the interview conducted by Adrian Onică in Timişoara in 2001, published in Memoria salvată, Evreii din Banat ieri și azi, coordinated by Smaranda Vultur, Polirom Publishing House, Iași, 2002.

FABRIC - IT'S ME

What strikes the foreigner coming to Timisoara is the presence in the city of several places with the appearance of centre.

The heart of the Fabric is Traian Square, fed by the street-veins that suddenly turn into arteries when you are forced to integrate into the flow away from this rectangular heart.

Compared to the years when I used to pass by daily (in fact, I was driven) a few times, a lot has changed, although the air of continuity is there. I'd give it to photos taken from different angles of the buildings, always ready to take flight. The reality is that it should be photographed at least every minute. One would also notice the movement of passers-by, and the way the light moves, on them and on the walls. One would also see the subtle but all the more dramatic grip of dusk, when a young soul grows flapping wings without fail, or rather, what is all the more sad, illusory flapping wings, stumbling among the grim walls, in the sullen, pragmatic routine of the individuals of the neighbourhood, whom one keeps seeing and seeing and seeing again.

It is amazing to me that the market continues to maintain itself even today, when I pass through it, once every few years, when I no longer give it my blood tribute, when I no longer proudly stretch from wall to wall, man to man, until the supreme exclamation "Traian Square - c'est moi!"

A vulcanisation workshop was set up where the workers' club used to be. The window through which I look gives me the illusion of age, of the accumulation of so many and so many images, but can you tell?! Here every evening something was broken, the thirsty senses carried their possessor (the possessed!) from one side to the other, following the signs of the vehemence, the uproar, the brawl, the apathetic background. This is where I first saw two authors of books, Mihu Dragomir and Nicolae Tăutu, where I measured them for a long time, where I experimented with their distances. Dan, my classmate, today a redoubtable Hispanist, recited in his ear, during the break, to the military writer the kilometric poem he had just finished in the P.A.P. (Preparation for the Defence of the Fatherland) or Russian class. Suspecting him of attempting to assert himself at any cost, I snorted indignantly at the line "desperation licks stones", while my friend's changing voice had taken on such truly exasperated overtones that I turned my back so I could let out a nervous laugh.

It was also here that I (a penultimate year high school student) witnessed for the first time a caft like in the movies, an integral part of the dance evening, between the neighborhood boys and the students, decided categorically in favor of the former. One student's nobly bloodied face, his arguments on innocence and nonviolence, developed in a beautiful flow, aroused my envy and crushing admiration, but also taught me a lesson - not to brag about my schools in front of the big and small thugs and bullies who dominated the area and with whom, for security reasons, I had to haver (pretender).

I was in a completely different mood when I couldn't intervene for the Bucovina man beaten up for no reason by the waiters in the basement beer hall. He, the uprooted, skinny saloon keeper, lost in his baggy trousers and huge rubber boots, had sung to us, a little earlier, with clear and unbearable despair, "That streinu-i ca pelinu / In the pewter you put sugar / But streinu is still bitter". Now he was slowly shying away from his assailants and begging them, in a halting voice, only to hit him on the head, to protect his stomach, because he had a nasty ulcer. And they got even angrier, slapped him in the head and in the stomach, so he wouldn't make any more demands. Finally, the militiaman appeared tactically and took out his report book, determined to hang the Bucovina man for disturbing public order.

The bakery is still there, with the same languid cakes in the window, but the summer garden is gone. This is where Genu and I would come around an exam and, suddenly fattening up the pig, we would pour the contents of a vial of caffeine into our juice so we could read all night.

Another famous cellar was on Anton Pann. In its place you'll come across the glass warehouse. We'd show up on New Year's Eve, get a small rum to set up. Young and old lumpens (mostly cokies, wagoners that is) were to spend in the not too deep hell, through the swirling of thick smoke and sounds imagining Romanian and Hungarian party tunes, whined by a warped old man and with nagging bubbles on his face to an outdated fiddle. Next came the goat people; in exchange for a three lei coin, the gypsy girl bared her breasts for a moment. We were leaving for the party rooms a little shaken, leaving them in the hands of unquestioning happiness.

There is no house left, on Marshal Joffre, the house of Kuliner Peter (who wrote miserably, but drew brilliantly, because he had taken lessons from the great Podlipny) and Hild Robert (who on Shabbat, despite the protests of the headmaster, stood alone for the duration of the lessons). In place of that house is a space, a gap between two blocks.

Viorel Marineasa, excerpt from the book O cedare în anii '20, Paralela 45 Publishing House, Pitesti, 1998.

Listen to the audio version.

"I arrived in Timisoara one autumn as part of a love story and didn't know what to expect from this city. I didn't know how it would receive me and if it would accept me but every day it let itself be discovered and sometimes, when I spoiled it, it let me admire the inside of a building or it would walk my steps along a side street full of leaves in autumn colours. On cool mornings we would warm up together over coffee in Unirii and in the afternoon he would let me go upstairs to greet an old friend who carried his Viennese perfume on through the antique shop. Sometimes I would wander through his streets and, as if to show me the way, he would send me to the German Bookshop or the "Cardinal Points" roundabout. I didn't want to leave the citadel and I would return under the walls of the Bastion only to find myself walking along the bank of the Bega with a rose on my lapel picked from the Rose Park. Sunset would catch me in the Cathedral Park, surrounded by the noise of crows and ravens, and then I would quickly run after the tram that led to Traian Square, wanting to satisfy my hunger with a small workman's snack and then the evening would end in the brewery restaurant with a misty blonde. This was how I spent my autumn days in cosmopolitan Temesvar."

Ionuț Caluian